Book Review - Mountains and Lowlands: Ancient Iran and Mesopotamia by Paul Collins

Review

Author: Petros Koutoupis

Originally published by Ancient Origins (7 January, 2017), but revised.

Mountains and Lowlands is published by the Ashmolean Museum at the University of Oxford. The author, Paul Collins, undertakes an extremely ambitious task of cataloguing over 6000 years of human history into a single 200+ page volume. A quick peak at Collins’ impressive curriculum vitae leaves no room for doubt that he is more than qualified for such a challenge. He is the Jaleh Hearn Curator for the Ancient Near East in the Antiquities Department of the Ashmolean Museum. He is a Fellow of both Jesus and Wolfson Colleges in Oxford while also a Fellow of the Society of Antiquities of London. Collins serves on the Council of the British Institute for the Study of Iraq. Again, quite impressive.

I appreciated the way in which Collins introduced the reader to the general Near East and more specifically, its more modern history and current affairs which continue to shape and reshape the always volatile region. While many civilizations have come, made their mark and gone, very little has changed over the millennia. The struggles of the people have evolved but they are still ever so present.

In recent years, it has become necessary to re-evaluate our modern understanding of the history of this region. Historically, scholars have often viewed and compared the ancient Near East against the Western world and the backdrop of the general Mediterranean. Collins makes it very obvious that he is attempting to correct this mindset.

After setting the scene, the publication follows a more traditional and chronological approach. Each chapter that follows covers a defining timeframe, starting from the earliest Bronze Age (6000 BC) and ending with the Iron Age (650 AD).

From the start, Collins does not waste any time. He immediately plunges the reader into the rise of scattered villages across the fertile valleys and the reasons why these ancient peoples started to form cities, thus creating our earliest civilizations. Often motivated by natural resources, cult, trade, and more, these early civilizations would begin to lay the foundation for many years to come.

It wouldn’t take long for competition to rise amongst these cities and with that competition also rose kingships and military might. Kingdoms would be carved and empires forged. Ruling dynasties toggling power back and forth from Sumer, to Akkad and back to Sumer. Their cultures and influences would begin to spread like wildfire across the known world. For instance, the Akkadian language and its version of cuneiform writing continued to persist as the lingua franca across the entire Near East, where it thrived as both a language of commerce and diplomacy. As these older nations disappeared, new ones rose from their ashes and in many ways continued worshiping the same gods of old and spoke a more modern variant of the languages. And where there are gaps in the historical record, the author did proceed with caution, rarely referring to ancient writers, for example, the Greek historian Herodotus. The book ends with the rise and influence of Islam.

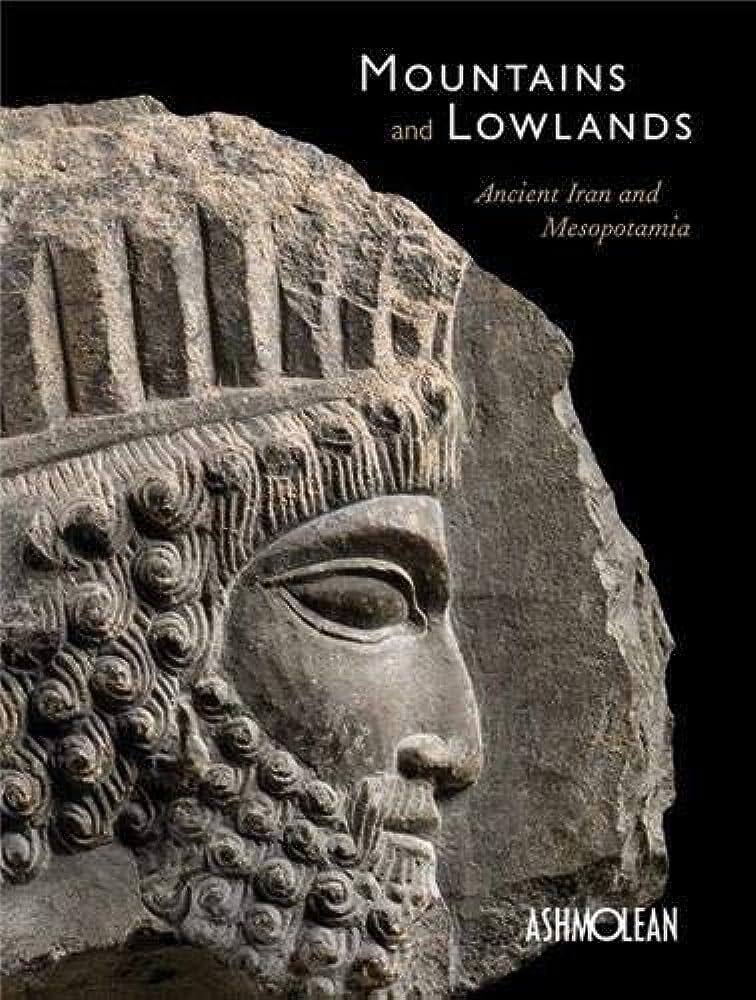

There is no doubt that this publication showcases some of the most beautiful photographs of ancient artifacts. Most of which are housed in the Ashmolean while the others vary in location from the British Museum, to the University of Pennsylvania, and even the Louvre.

I found this research to be very fascinating and an extremely well compiled collection covering pretty much everything you need to know about both ancient Mesopotamia and Iran. I highly recommended it to those with an interest or passion on Near Eastern history.

You can purchase a copy of Mountains and Lowlands at Amazon.