Elam: A Kingdom Ahead of Its Time

Featured Article

By Jess Nadeau

At the dawn of civilization, nestled at the foot of the Zagros Mountains, overlooking the vast Iranian plateau, the ancient city of Susa was founded. It did not form from the will of any single entity, but rather a union of diverse villages that inhabited the surrounding region. As one of the first known settlements in the world (c. 4200 BCE), it quickly flourished as a cradle for advancing technologies, architectural feats, artistic expression, political power, religious worship, and the development of writing.

It was because of this indigenous diversity and cooperation that Susa would become such a remarkable example of cultural proliferation during a time when urbanization was merely in its infancy. By c. 3200 BCE, the kingdom of Elam was born, one that spanned thousands of years and four time periods. And it was during these prolific periods that some of the most innovative yet perplexing archaeological discoveries were uncovered, enigmas that continue to defy explanation and challenge scholarly opinions.

A History of Innovation

Etymologically, the name Elam derives from the Akkadian and Sumerian words for highlands or high country. For the people of Elam, the Elamites, they called their country something of a similar meaning, Haltamti. Though Susa formed the foundation of their society, the Elamites were never a cohesive group in the traditional sense, building neighboring capitals like Awan, Anshan, and Shimashki. Each city had leaders and principal deities, but together, they functioned as an integrated federation. However, Susa is often remembered as the heart of Elam. Its prominence as a trade center—reaching into Mesopotamia and far to the east into India—along with its acquired wealth and towering presence, made it a strategic powerhouse. For modern archaeologists, Susa is the single most vital resource in artifacts, monuments, and inscriptions.

The Proto-Elamite period lasted roughly from 3200 to 2700 BCE. This era is steeped in mystery, largely due to its unique language and writing, one that is an isolate to all other developing societies. In truth, several incredibly profound things happened during the proto-era. Aside from being one of the first societies to develop a written language, the Elamites were unequivocally skilled in their artistic endeavors. Their work exhibits qualities unique to the world. Rather than anthropomorphizing their deities like so many others, they appeared to have made the animal the focal point and did so with astonishing detail and craftsmanship. Additionally, they crafted exquisite jewelry, ceramics, metalworks, and impressions.

It was also during this time that the Elamites found themselves among the chronicles of neighboring powers. Documented as the first war in recorded history, a fierce battle erupted between the Sumerians and the Elamites sometime around 2700 BCE. Though brief, an account mentioned in the Sumerian king list proclaims, “Enmenbaragesi, who made the land of Elam submit, became king; he ruled for 900 years.”

Despite the loss, the Elamites would go on to establish a glorious kingdom. By the Old Elamite period (c. 2700 – 1600 BCE), their royal dynasties were recognized and honored, each ruling from their respective capital (Awan, Anshan, Susa). The Akkadians temporarily conquered and occupied Awan and Susa, but were later driven out by the Gutians, a West Asiatic people, who were, in turn, expelled by the Sumerians. Soon, the Elamites banded together with the Amorites, sacked the city of Ur, took the king as a prisoner of war, and regained control of their region. Thereafter, they began fiercely asserting themselves. They assembled a formidable army, expanded on their territories, acquired plentiful resources, and cultivated relationships. Even so, relationships are often fleeting, as such with Hammurabi of Babylon. After advantageously utilizing Elam to conquer Mesopotamia, he quickly turned on them and claimed the region as his own. But the Elamites were eternally resilient.

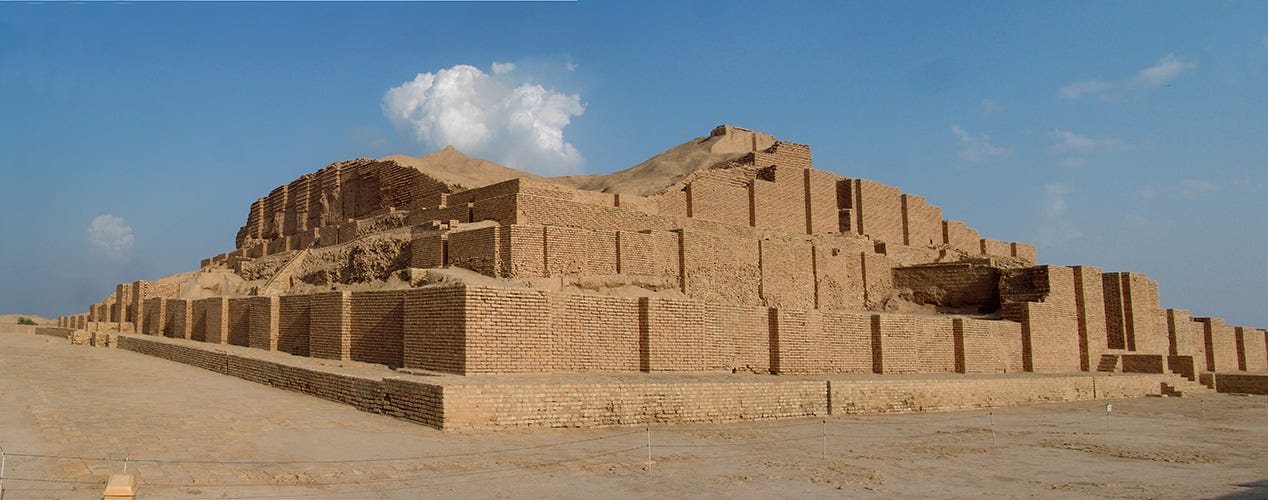

Into the late Old Elamite period and Middle Kingdom (c. 1500 – 1100 BCE), their religion, culture, and language dominated the region. Their religion grew exponentially, encompassing over 200 deities throughout the kingdom and numerous sacred sites atop mountains and hills, and hidden within lush groves. Kings built temples and monuments to legitimize their rule, to ensure strength, prosperity, and military might. During the Middle Kingdom, a grand temple complex was built, one that attested to Elam’s admirable acceptance of all deities worshipped throughout the kingdom. Dur-Untash was unlike any religious center known to history. It housed sacred sites to the gods of Awan, Anshan, Susa, Mesopotamian city-states, and a few likely others. Encircled by an impenetrable wall, the lofty ziggurat rose to the heavens as a haven dedicated to the care of holy statuary. Its imposing aura did not last, however, as soon as the king who built it perished, it was inexplicably left abandoned.

Perhaps, it would be worth mentioning a bit about the Elamites’ extraordinary and sizable pantheon. To begin, they certainly placed great significance on the afterlife. Archaeological evidence suggests that they took great care in aiding their dead through their transition by divine procession, inscriptions of safe passage, and prayer. Since there are no known descriptions of the Elamite afterlife, one could only suspect that they may have adopted aspects from Mesopotamia—they did incorporate several of their deities into their pantheon—or possibly the Egyptians, who placed such significance on the afterlife. Other influences may have come from the religions of the Iranian plateau or even the Indus Valley they so frequently traded with.

Their gods were cosmic lords, judges of the dead, guardians of kings, queens of heaven and the immortal soul. Simut was the god of Elam; Insushinak, Lord of Susa; Humban, Lord of Anshan. Kiririsha was the wife and consort of both Humban and Insushinak, and the mother of the gods. Napirisha was their supreme god, Lord of the earth and all its people. Interestingly, similar to Mesopotamia and Egypt, the kings of Elam also incorporated the names of these all-powerful gods into their own.

For a time, it seemed the Elamites would prevail, but like most societies of the era, chaos loomed. Briefly, they established an empire, reaching into Mesopotamia, but feuding amongst family brought it to a swift end. The Neo-Elamite period (c. 1100 – 539 BCE) brought the Assyrians and later the Persians to their gates. Inevitably, they were absorbed into the Achaemenid Empire under Cyrus the Great in 539 BCE. Yet, as I said before, the Elamites were a resilient people, and the Persians found a source of inspiration in them. They rebuilt Susa, which had faced near destruction during the Assyrian invasion, and preserved their art, culture, and traditions. Their ambiguous uniqueness is really what sets them apart and subsequently spared them from vanishing from the annals of history. However, their history can only reveal so much—there is always more to learn beneath the surface of records, of wars, pantheons, and political powers.

Deciphering the Undecipherable

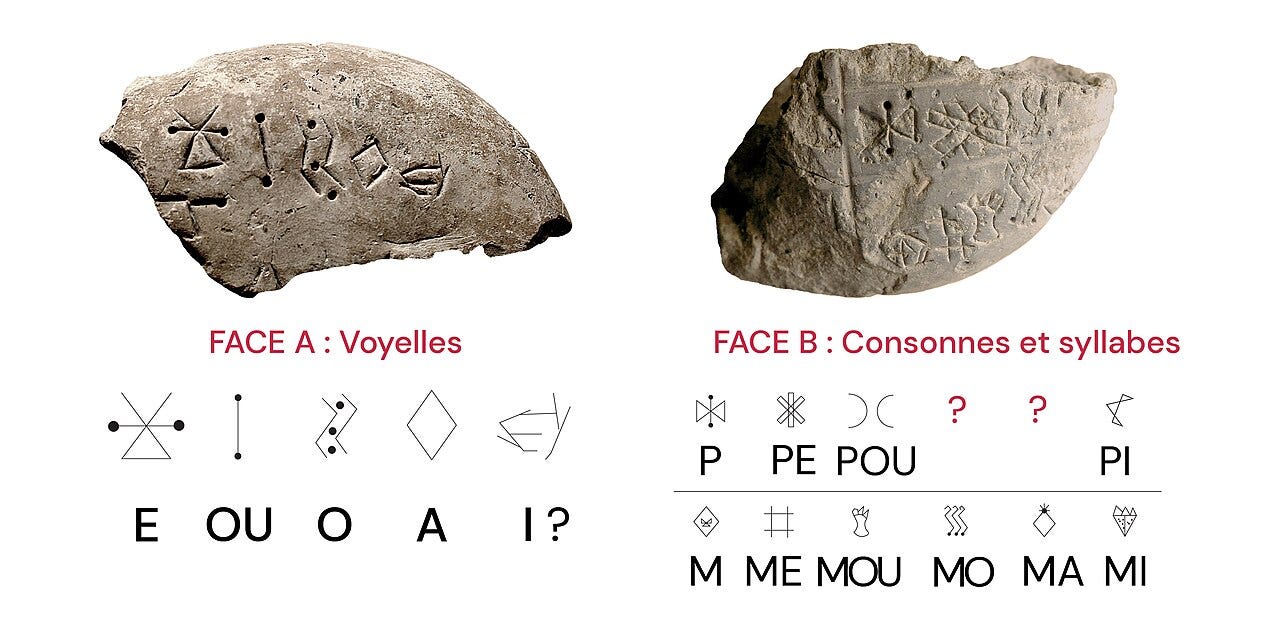

To this day, very little is known about the Elamite language. For over 3000 years, the language was spoken, but no scholar has been able to replicate it. This is largely due to it being a language in isolate, meaning that it is unrelated to any other language family. Around the time that the Sumerians were developing one of the first known written languages, cuneiform, the Elamites were doing much the same. Proto-Elamite script was developed in its early era (c. 3200 – 2700 BCE), likely used by scribes for administrative purposes and the like, gradually to be replaced by cuneiform as the Elamites were introduced to the Akkadians. Nearly 800 years later, and quite suddenly, the Elamites developed a new script, commonly referred to as Linear Elamite, but it, too, disappeared during widespread societal collapse at the end of the Bronze Age.

Archaeologists have managed to acquire around 1600 inscriptions of Proto-Elamite script and approximately 43 in Linear Elamite, mostly originating from Susa. For the past century, scholars have worked tirelessly to decipher them with slow progress. And debates continue as to whether or not the two scripts are even related, one being the basis for the other. In 2015, this conundrum looked as if it might be solved as a French archaeologist by the name of François Desset got his hands on a collection of privately owned silver vessels. The vessels in question purportedly came from a royal cemetery dating back to c. 2000 BCE and had evidence of Linear Elamite script along with cuneiform translations. Initially, the authenticity of the vessels had been criticized, but later analysis revealed they were indeed authentic.

For scholars, this remarkable find would prove fruitful. Desset and his team of researchers were able to decipher the names of kings and several verbs. Over the next several years, according to Desset’s 2022 published study, the team was able to accurately translate up to 96% of known Linear Elamite symbols, equating to about 72 symbols. Yet, with so few inscriptions, this only scratches the surface. So much is left unknown, including translating a select number of symbols into the complexities of a fully discernible language.

Though many have hailed Desset’s findings as groundbreaking, some of his other arguments have been a bit controversial. He claims that Linear Elamite is phonetic, the first of its kind, contrary to the Phoenicians, who developed a phonetic alphabet in c. 1100 BCE. Desset also claims that Linear Elamite originated out of Proto-Elamite, an argument that has been made before in the early 20th century. Nonetheless, without substantial sources and an 800-year gap between each script, there is little to work with.

Further arguments place the development of Proto-Elamite at the time of cuneiform, which has its likelihood, but Desset asserts that they developed independently of one another. As fascinating as all this sounds, it has yet to be widely accepted. The consensus is that yes, Linear Elamite does appear to be phonographic in that the symbols represent a sound, but its predecessor, Proto-Elamite, does not share the same qualities and may or may not be related. It would appear that Proto-Elamite does display phonographic qualities, logograms, numerical values, and possibly ideograms, which suggests that it used syllables and pictorial representations of words. This is oddly reminiscent of the Egyptians, who used a combination of syllables, ideograms, and logograms to convey sounds, words, and ideas or concepts.

This is all intriguing, to say the least. Early forms of cuneiform used primarily logograms with very few phonographic elements, which were expanded upon by the Akkadians. If Linear Elamite is phonographic, then it would be an extraordinary advancement in written language that changes the way the world has commonly understood its evolution over time. Proto-Elamite, on the other hand, has yet to be deciphered. Only a handful of expressions have been translated, while the vast majority of it is relatively undecipherable. Theories and speculations abound point to a fellow undeciphered script, the Indus Valley script, or a link between the Elamite language and the Dravidian language family of Northern India, referred to as the Elamo-Dravidian hypothesis (1975). To some extent, it may fit, given that there was trade among the two groups and influences are expected. Others suggest that Proto-Elamite shares commonalities with proto-cuneiform, a more acceptable relationship.

Despite more than a century’s worth of collaborative efforts, it seems that Proto-Elamite or the Elamite language will not be fully deciphered any time soon. Thankfully, we have been able to learn a bit more about the Elamites through their linear script, but that continues to be a work in progress. As we know from history, many shifting elements swept through the region, and influences may have come from other powers or the Elamites themselves. To what degree these early groups influenced each other is debatable without ample evidence. Though, there is one question that lingers on the minds of Desset and his team, as well as all others that study Elam: what accounts for an 800-year gap between the language scripts? Maybe future discoveries will find an answer to the perplexities we have yet to fully understand.

The Son of the King’s Sister

As intriguing as deciphering the undecipherable may be, there is yet another aspect of Elamite society that sparks debate, that being their system of succession. It all stems from a single phrase, “son of a sister.” But why has this phrase caused quite the stir among the academic community? Simply put, it was used as an epithet to a number of Elamite kings, with foggy implications. For a time, it was accepted that this term must have meant that the Elamites practiced a matrilineal succession system, as in the son of the king’s sister would inherit the throne. Later scholars have since argued that the usage of this term can only imply that the Elamite royals participated in incestuous unions to keep bloodlines pure and ensure power remained within the family. The incest theory appears to be the dominant and widely accepted theory as of today. Yet, other scholars find it problematic for a couple of reasons: it takes the phrase at face value and neglects to consider an ambiguous cultural context, which is arguably ethnocentric.

First and foremost, scholars of an alternative theory point out that we must consider in what context these statements were made. Most of the inscriptions referring to the king as the son of a sister originate from Susa in the early second millennium BCE, with around eleven kings named as such. During the Middle Elamite period and the Neo-Elamite period, only a select few used this epithet. In another inscription, the king refers to himself as the son of the three kings that preceded him, as if he had three different fathers through a single mother. This may support the incest theory, but it may also point to something far more common throughout the world.

Now to consider what type of identification system the Elamites may have used. If they were to use a straightforward descriptive system, then referring to the king as the sister’s son and the several preceding kings as fathers could be taken literally. If their system was a broad classification, then fathers and sisters could represent several female and male relatives, all using a culturally constructed term with symbolic meaning to kingship. And this is not by any means something out of the ordinary. Some indigenous cultures of the Americas, Oceania, and surely others have been known to consider all male relatives of the father’s matrilineal line, including uncles and the fathers before them as fathers, similarly with sisters. Therefore, familial affiliations were not literal, but grouped in symbolic terms that reflected the importance of relationships within a tribal context.

It is generally understood that the founding of Susa emerged with the convergence of several local tribal communities; therefore, if we take into account ancestral tribal affiliations, it may be yet another indication of symbolic meaning placed on the title of father or sister within the context of kingship. As an example, the term father used to represent multiple past rulers may indicate an affiliation more closely resembling that of an ancestral cult that functioned as a way to embody the exceptional characteristics of those who came before him.

Scholars also point to the known history of special privileges placed on the son of the king’s sister. This could be seen as preferential status, as in medieval European literature like Beowulf, who was the heroic son of the king’s sister. More specifically, it may be seen in royal succession. The Scottish Picts of the 3rd through 9th century CE were generally believed to have practiced this type of succession, granting the sister’s son kingship. People throughout Sudan and the eastern deserts of Egypt have also been known to do the same. Additionally, the Trobriand Islanders of Papua New Guinea have a long, well-documented history of matrilineal practices and succession. What’s more convincing still are those who lived just north of Elam around 708 BCE. Historical records from the kingdom of Ellipi gave mention of two sons of the king’s sister who had feuded over the throne after the king died, absent any consideration of the king’s children.

One might ask the reasoning behind placing preferential status on the son of the king’s sister. Ancient Roman historian Tacitus, when commenting on the city-states of Germania, had said that the children of the king’s sister were held to the same regard as the children of the king, perhaps even more so. In the case of hostages being taken, the children of a king’s sister would have a stronger hold on the family. In societies that place a higher status on the sons of the king’s sister, the reason is often much simpler than one might expect: the children of the king’s sister are guaranteed to carry his blood, whereas his own children have the potential to be the product of another man.

Some have even gone so far as to propose that the kingdom of Elam was a matriarchal society, founded by a woman, only later to become patriarchal, which explains the significance placed on the sister’s son and the matrilineal line. However, there is no evidence to support this claim, and still little evidence to support any of these arguments. Tacitus, even after implying choices made during hostage situations, continued to say that only a king’s child should be his heir. So, what to make of all this? Neighboring regions, like the Egyptians, Romans, and others, were fully accepting of incestuous marriages within the royal family. Matrilineal succession was also a known practice throughout the world, all the same with tribal affiliations, ancestral cults, and symbolic familial epithets. Though modern scholars may hold steadfast to the incest argument, there is no clear answer without direction—every theory has its likelihood.

Gone, but Not Forgotten

Perhaps Elam was before its time, a kingdom of rich histories that may never be fully revealed. Most of what is known of Elam comes from second-hand sources: the Akkadians, Sumerians, Assyrians, and biblical texts that gave them a place among the lands of Noah’s sons. There are few sources that are original and decipherable. Archaeological limitations, cultural shifts and evolving influences, and an isolated language and script, all make for an incredibly fragmented and mysterious culture. Theories and speculations may remain just that, with no consensus as to the lives of their rulers and the realities of their people.

Still, not all is lost. What little is known paints an inspiring picture of a people whose craftsmanship, wealth, adaptability, advancements, and quite possibly regard for women as equals leave a lasting impression. After being absorbed by the Achaemenid Empire, the Elamites never vanished but were embraced, eventually becoming the predecessor to the Persian culture. Their legacy lives on in more ways than we can imagine, a truly resilient people indeed.

Featured Image: An Ancient Elamite Ziggurat. (Shee Heng Chong / Shutterstock)

References

Mark, J. 2020. Elam. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/elam/

M, J. 2020. Ten Ancient Elam Facts You Need to Know. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1591/ten-ancient-elam-facts-you-need-to-know/

Lawler, A. 2022. Have Scholars Finally Deciphered a Mysterious Ancient Script? Smithsonian Magazine. Available at: https://www.smithsonianmag.com/history/have-scholars-finally-deciphered-a-mysterious-ancient-script-180980497/

Potts, D. T. 2023. Problems in the Study of Elamite Kinship. Aspects of Kinship in Ancient Iran, Chapter 3. University of California Press. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1525/9780520395015-006

The Sumerian King’s List: Translation. The Electronic Text Corpus of Sumerian Literature. Available at: https://etcsl.orinst.ox.ac.uk/section2/tr211.htm

What does it say about us humans that where civilizations began has been a war zone ever since? Fascinating essay.

Fantastic essay. Fell in love with the ancient history of that region after reading Metropolis (Ben Wilson) and The Silk Road (Peter Frankopan)

Similar to Robert’s comment.. it is tragic that this entire area is now the source of such turmoil.