Featured Article - A Paradise Lost: In Search of Eden

Issue 21

Author: Petros Koutoupis

Originally published at Ancient Origins (4 July, 2014) but revised.

Nothing else has fascinated both archaeologists and theologians alike more than the identity to the location of man’s paradise lost; that is, the Garden of Eden. Throughout history, the idea of a paradise was a common theme in almost all ancient cultures. The Sumerians called it Dilmun (commonly identified as the modern day island of Bahrain). The Greeks called it the Garden of the Hesperides. The idea was not a unique one to the Biblical author(s), however the Book of Genesis does provide us with the most details; albeit vague, to its location. What was Eden and where was it located? We will need to dive through the ancient sources at our disposal so that we may decipher the enigma that is Eden.

Genesis 2:8-9 informs us of a garden set to the east, trees and animals a plenty, which a river flowed through and parted into four: Pishon, Gihon, Tigris and Euphrates. The Septuagint (or LXX) confirms the translations of the Tigris and Euphrates, although the Pishon and Gihon continue to remain a mystery. The identification of the two rivers have led many to look to Mesopotamia and more recently the submerged regions of the Persian Gulf, although how much of these details can we consider to be credible?

It would seem that geography was not the author’s strongest feature. For instance, we know where both the Tigris and Euphrates meet in southern Mesopotamia and where the rivers flow to in the North and Northwest. As for the river Gihon, a literal reading of Genesis 2:13 from the Hebrew source translates to: ‘And [the] name [of] the second [is] the river Gihon. It circles around all [the] land [of] Cush.’ We clearly read that Gihon flowed from the Persian Gulf and parted to circle Cush. According to Hebrew and Assyrian source, Cush is identified as Ethiopia. Yes, the very same Ethiopia that resides on the separate continent of Africa. For this reason, many have identified the river Nile with Gihon, although such an identification would invalidate the original statement in that it parted alongside three others from the same river. Coincidently, 1Kings 1:33 mentions a spring near Jerusalem by the name of Gihon. The Hebrew name translates to ‘bursting forth,’ a generic term that can describe just about anything.

When we read beyond the Book of Genesis, we do find additional references to Eden (Jewish Publication Society or JPS translation):

Isaiah 37:12: Have the gods of the nations delivered them which my fathers have destroyed, as Gozan, and Haran, and Rezeph, and the children of Eden which were in Telassar?

Ezekiel 27:23: Haran, and Canneh, and Eden, the merchants of Sheba, Asshur, and Chilmad, were thy merchants.

Ezekiel 31:16: I made the nations to shake at the sound of his fall, when I cast him down to hell with them that descend into the pit: and all the trees of Eden, the choice and best of Lebanon, all that drink water, shall be comforted in the nether parts of the earth.

Does this mean that Eden was still around at the time the Book of Ezekiel was written (during the Babylonian Exile)? Isaiah speaks of the children of Eden as a nation that still existed, while

Ezekiel hints at Eden being a merchant town. It is listed along with other locations situated in northern Mesopotamia, southern Anatolia and the northern Levant. Does this hint at Eden being located somewhere within this outline? When we reread Ezekiel 31:16, we observe the verse confirming that Eden is in the land of Lebanon, a region well renowned for its cedars.

This is further confirmed when identifying the proper etymology for the name Eden. Traditionally, scholars believed it to be a Hebrew rendering of the Sumerian word edin translating to ‘steppe.’ Archaeology, however, has shown this word to be Aramaic in origin, a Semitic language, widely used to the North of ancient Israel and in ancient Lebanon and Syria.

Discovered at Tell el Fakhariyah (on one of the tributaries of the Khabur River), Syria in 1979, was a statue containing a bilingual inscription. Dating to approximately the late 9th century BCE, the statue provides the oldest evidence of the Aramaic language. Written on the skirt of the man, the bilingual inscription was inscribed in Assyrian cuneiform and the Semitic linear alphabet in an Aramaic dialect. It is this bilingual text that holds the key to the earliest identification and interpretation of the word ‘eden.’ Used as a verb, ‘dn corresponds to the Assyrian verb for ‘wealth or luxuriance.’ This translation reinforces the idea of a paradise behind the Genesis narrative.

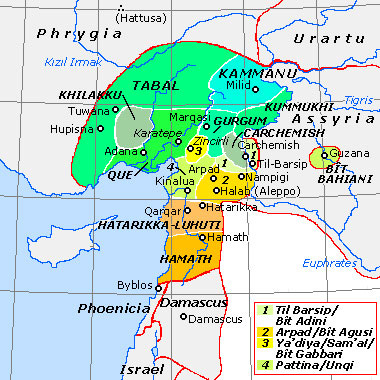

Despite this extraordinary discovery, Assyrian sources provide more clues to the location of Eden. Assyrian records have revealed the identification of an Aramean state that thrived between the 10th - 9th centuries BCE. The name of this kingdom was Bit Adini (or House of Eden) and its capital was centered at Til Barsip (modern day Tell Ahmar). Bit Adini would be conquered and absorbed into the Neo-Assyrian empire in 856 BCE, during the reign of Shalmaneser III (reigned between 859 - 824 BCE). Located in Syria, Til Barsip was situated along the Euphrates River. It is now that the cryptic passages in Ezekiel and Isaiah, and the general location for Eden, are coming together.

The Book of Isaiah sheds light on the outcome of the people who inhabited Eden. As was the outcome of many nations who opposed the Assyrians and later Babylonians, the conquered would be exiled to the furthest reaches of the empire. In the early 9th century BCE, an Aramean coalition was formed which opposed the Assyrian war machine. Ashurnasirpal (reigned between 883 - 859 BCE) would quell this rebellion until his son Shalmaneser conquered and absorbed the region. During this period, people would have been exiled and Assyrian citizens would resettle in the newly conquered territories. The Edenites, alongside the people of Haran, Gozan, and Rezeph were transported to Telassar. Translating to ‘Assyrian hill,’ Telassar was a city conquered and held by the Assyrians. Written in the Assyrian and Babylonian Chronicles as Til-Assuri, it has been identified with Bit-Burnaki (also written as Bit-Bunakku) in Elam, to the East of Mesopotamia in modern day Iran.

How does this relate to the Garden of Eden in the Book of Genesis? I for one, believe the narrative to be an allegorical one; possibly intended as propaganda. It was inspired by the Assyrian expansion and the many people exiled, to never return to their homeland (i.e. Adam and Eve’s expulsion to the East). What may confirm this claim is a verse found in Genesis 3:24 (JPS translation):

So He drove out the man; and He placed at the east of the garden of Eden the cherubim, and the flaming sword which turned every way, to keep the way to the tree of life.

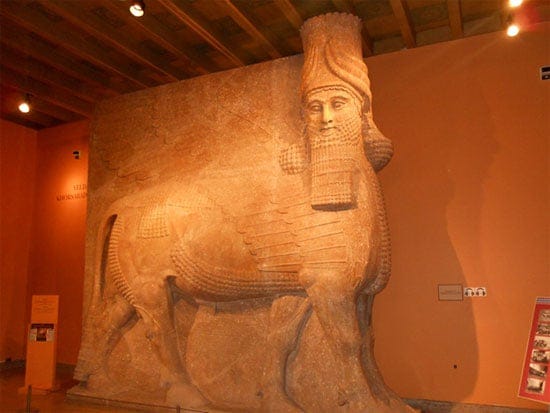

After becoming part of the Assyrian empire, the once capital of the Edenites, Til Barsip was Assyrianized. It was once decorated with beautiful art consisting of rosettes, royal processions, hunting scenes, to even the lamassu. The lamassu (also referred to as a shedu and the Akkadian kuribu), was a divinity with the head of a man and the body of a bull. They typically stood as guardians, usually in the king’s palace and throne room. These lamassu are one and the same as the Hebrew cherubim. While a common piece of decoration in Levantine art, it was more commonplace within Assyrian and Babylonian cultures. The stationing of the cherubim as guards to the garden may be symbolic of the Assyrian influence and occupation of Til Barsip. How should we interpret the Tree of Knowledge of Good and Evil and the Tree of Life? Mystical trees are not uncommon to Assyrian imagery. This includes a very well-known relief with Ashurnasirpal flanking both sides of the Tree of Life. As for the garden itself, I am reminded of the recently published articles claiming the Hanging Gardens of Babylon to be located to the North in Nineveh, a once Assyrian capital, and constructed during the reign of Sennacherib (reigned between 705 - 681 BCE). Apparently, Assyrians loved their gardens.

Sources

Brenton, Lancelot C.L. The Septuagint with Apocrypha . Peabody: Hendrickson Publishers,1986. [Print]

JPS Hebrew-English Tanakh . Philadelphia: Jewish Publication Society, 2003. [Print]

Koutoupis, Petros. Biblical Origins: An Adopted Legacy . College Station: Virtualbookworm.com P, 2008. [Print]

Millard, A. R. and P. Bordreuil. “A Statue from Syria with Assyrian and Aramaic Inscriptions.” The Biblical Archaeologist, Vol. 45, No. 3. 1982: 135-141. [Print]

Rogers, Robert W. A History of Babylonia and Assyria: Volume 2 . Long Beach: Lost Arts Media, 2003. [Print]