Featured Article - In Search of the Mythical King Minos, Did the Legendary Ruler Really Exist?

Issue 42

Author: Petros Koutoupis

Originally published by Ancient Origins (6 January, 2018) but revised.

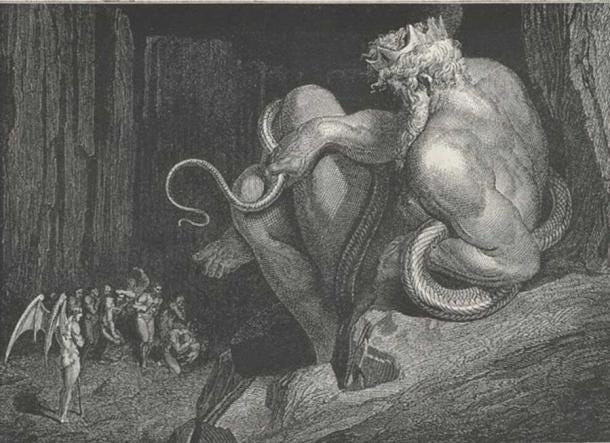

When we think of Minos, two images immediately come to mind: (1) the legendary and cruel tyrant of Crete who demanded the tribute of Athenian youths to feed to the Minotaur in the Labyrinth and (2) a judge of the Underworld as depicted in both Virgil’s Aeneid and also in Dante Alighieri’s Divine Comedy story, the Inferno. For the purpose of this article, we will focus on the former rather than the latter.

Who was King Minos?

According to both Greek myth and legend, Minos was an ancient king of the Greek island of Crete, situated in the Mediterranean Sea just South of the Greek mainland.

The earliest literary reference to the monarch dates back to at least the 9th century BCE in both Homeric epics, the Iliad and Odyssey. And it is just that, a reference with very little context:

For Zeus at the first begat Minos to be a watcher over Crete, and Minos again got him a son, even the peerless Deucalion, and Deucalion begat me, a lord over many men in wide Crete; and now have the ships brought me hither a bane to thee and thy father and the other Trojans.

Iliad (Book 13.450)

“And Phaedra and Procris I saw, and fair Ariadne, the daughter of Minos of baneful mind, whom once Theseus was fain to bear from Crete to the hill of sacred Athens…”

Odyssey (Book 11.321)

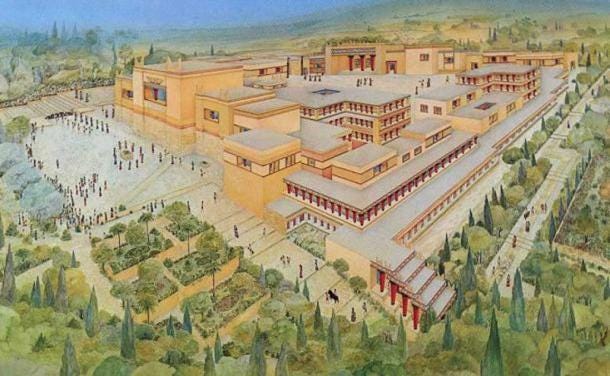

Minos ruled from his throne at Knossos, located to the central Northern coast of the island. He commanded a large and powerful navy which oversaw all trade throughout the Aegean and even held influence further East in both Canaan and Egypt. Named by archaeologist Sir Arthur Evans after the legendary king, the Minoans would continue to occupy the Aegean throughout the Bronze Age and until approximately 1400 BCE, that is, when the mainland Mycenaean Greeks overtook the island and in turn, their entire sea-based dominion.

King Minos Requests Plague and Hunger

After a series of events in the story surrounding Minos, the Cretan monarch subjected the city of Athens on the mainland to his rule and asked the gods to bring plague and hunger to its citizens. An oracle would later reveal that the only way to lift this punishment from the people of Athens was to give into Minos’ demands: “send seven boys and seven girls to Crete every nine years to be sacrificed to the Minotaur.” The Minotaur, a half-bull and half-human hybrid, lived on the island of Crete in a labyrinth built by the mythical architect, Daedalus. The creature would one day meet its end at the hands of Theseus.

It has been theorized that the name Minos was used as a title, similar to that of Pharaoh or Caesar. There may have been an original monarch bearing the name, but later kings would assume the title, to emulate the first. But whatever its use-case, it no doubt was a well-known epithet utilized by both the Greeks and even Egyptians in later literature. Obviously, as highlighted above, the Greeks would create an archetype or model of a single individual who would occasionally make a cameo appearance in their mythological stories. The Egyptians on the other hand, may prove this theory correct.

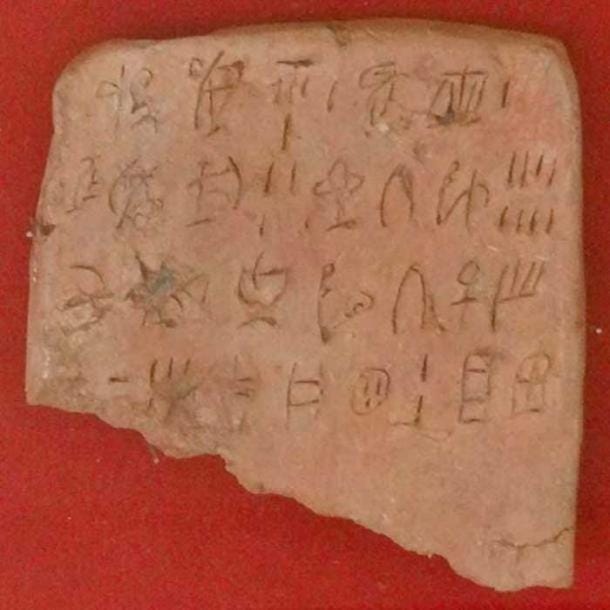

Egyptian texts during the New Kingdom Period (1550 - 1070 BCE) often referred to the island of Crete as Kaftu or Keftiu (Akkadian kaptaru and Biblical Caphtor). But in some cases, it is paired with the name Menus, a possible rendering of Minos. During the reign of Ramesses III (1186 -1155 BCE), there are times when Menus is written without the other (Cline, 152). Was this the Egyptian way of identifying the island and its people under the name Minos? Does this also imply the existence of a historical Minos or a title inherited by the later Cretan kings?

Sources

Cline, Eric H., David O’Connor. Ramesses III: The Life and Times of Egypt’s Last Hero. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan P, 2012. [Print]

Homer. The Iliad.

Homer. The Odyssey.