Featured Article - The Lemnos Stele: Etruscan or Remnants of a Shardana Colony?

Issue 50

Author: Petros Koutoupis

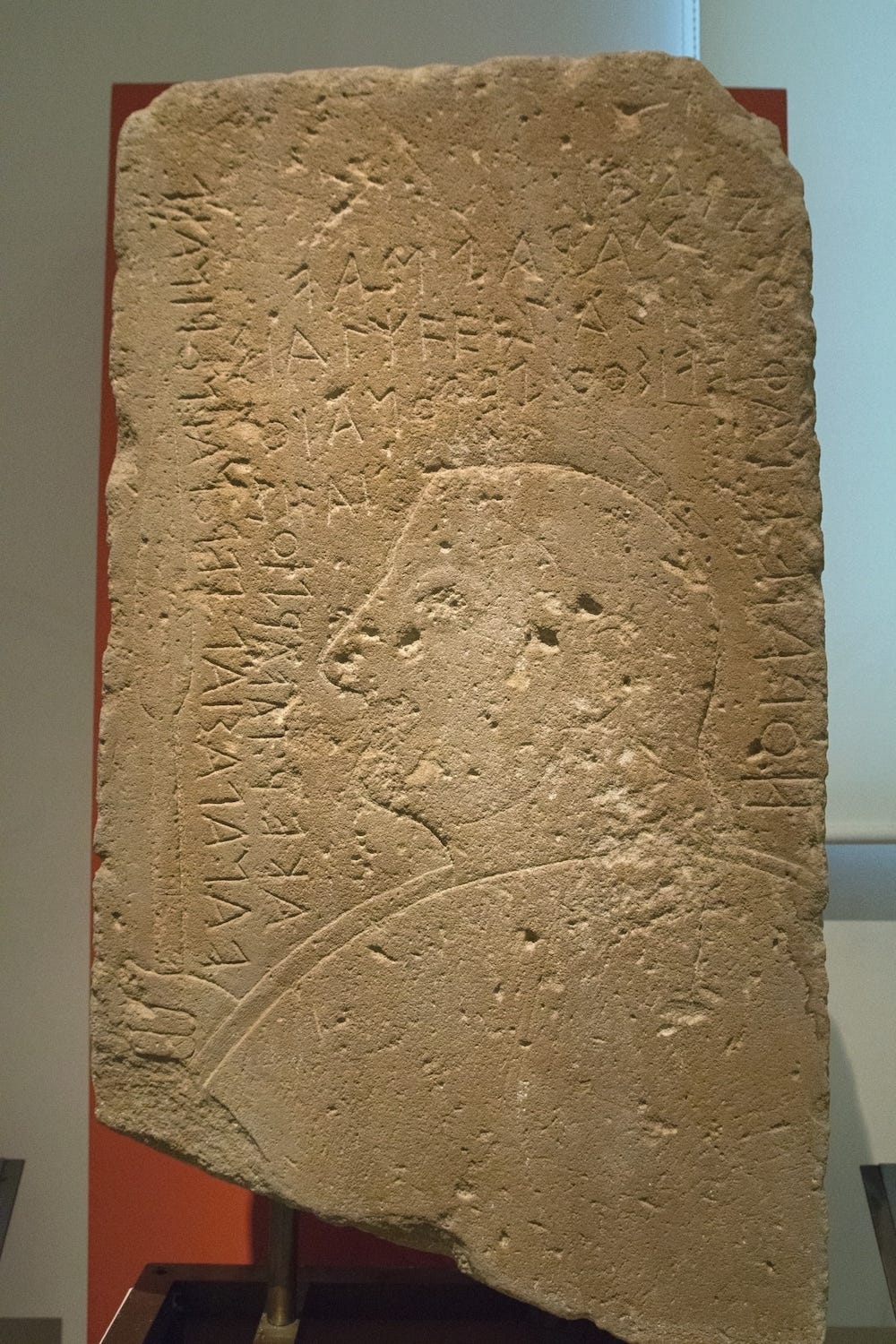

The Lemnos Stele was discovered or I should say, found built into a church wall in the village of Kaminia, located in the northeast part of the island of Lemnos, in the Aegean. The stele is currently housed in the National Archaeological Museum of Athens. It is believed to date to the second half of the 6th century BCE. What makes the inscription so important is the fact that despite using letters of the Greek alphabet, it isn’t written in Greek. It is now believed that the language on the stele is either Etruscan or related to the Tyrrhenian family of languages, of which Etruscan is classified. That being the case, there is now a pending question: how did a peoples originating from the Tyrrhenian region (of Western Italy) find themselves on the island of Lemnos.

The Mysterious Etruscans

The Etruscans emerged in what was Etruria (modern day Tuscany) in the Western and central regions of Italy, North of Latium. Their civilization extended from the Po Valley down to the boundaries of ancient Latium (D’Amato, The Etruscans, 4). While their origins are continuously debated in the academic world, one thing is for certain, we can trace their culture to as early as the 10th or 9th century BCE. By the start of the 6th century BCE, they emerged as a great power and their influence and art would be shared with the rest of the Mediterranean world. The Etruscans were contemporaries of the ancient Greeks, the nations of the Near East, Carthage and later in history, Rome (Bonfante, 7). The Etruscans were a powerful force with a strong navy and were masters of the sea.

The difficulty in understanding the Etruscan culture stems from the fact that not much of this culture survived. They originally referred to themselves as the Rasenna and centuries later, this evolved to Ransa. The name Etruscan was given to them by the later Romans. Despite deciphering the unique Etruscan language, very few inscriptions using a similar alphabet introduced by ancient Greek merchants have been discovered, and of the few discovered, leaves us with more questions than answers to this enigmatic group of peoples. Besides, these inscriptions never give us insight into the culture itself, only their rituals which were even foreign to their neighbors of the time. What makes matters worse is that the Classical and biased writers tended to portray the Etruscans in a negative light.

A lot of Etruscan architecture, mythologies, deities, and artistic style was adopted and adapted from the neighboring Greeks. From Homer’s greatest epics to the triumph of the gods over the Titans, the Etruscans were enjoying a lot of the same stories already spreading throughout the Mediterranean, the most important of which was the Iliad. Etruscan tombs to household items were decorated with scenes of the Iliad, whether it be the Judgement of Paris when Turms (Hermes) brings the three goddesses, Menerva (Athena), Uni (Hera) and Turan (Aphrodite), to Elcsuntre (Alexander), who will judge the beauty contest or the ambush of the Trojan prince Troilos, where Achle (Achilles), armed with a sacrificial knife hides to kill the unarmed youth (Bonfante,12, 18). This is not to say that the Etruscans did not have their own local myths. In fact, they did but the influence by the Greeks was very apparent.

During the 4th century BCE, Rome was expanding beyond Latium and started to annex Etruscan cities. By the 3rd century BCE, Rome completely conquered Etruria. During this entire process, the Romans adopted many Etruscan customs, mythologies, and art while leaving the rest to be forgotten to time. It has been a very difficult process for the modern scholar to identify what aspects of Roman culture, belief, and craft stem from the Etruscans. The only purely undisturbed window to this culture survives only in their lavish tombs.

Prior to their assimilation into Roman society and complete disappearance, Greek and Phoenician inscriptions record alliances and naval battles between the Etruscans and the Greeks of the Aegean and Magna Graecia (most Southern part of the Italian mainland below Latium). It was their established thalassocracy over the Tyrrhenian Sea that made the Etruscans a force to be contended with. Their mastering of the sea influenced future Roman seafaring.

The Sea Peoples

Nothing fascinates me more than the topic of the Sea Peoples. There is so much we know and yet, not enough. Our sources on this topic are quite limited as scholars tend to lean more on archaeology and ancient Egyptian inscriptions. I will touch on a third source further below. So, who were the Sea Peoples?

This is not a simple question to answer but in summary, the Sea Peoples (or Peoples of the Sea) were an enigmatic confederacy of seafaring raiders from the central and eastern Mediterranean who sailed East and invaded Anatolia, Syria, Canaan, Cyprus, and Egypt toward the end of the Bronze Age (ca. 1200 BCE). The term used to refer to these foreign migrants is derived from ancient Egyptian sources in which we have numerous documented accounts of battles involving them. It should be noted that not all of the Sea Peoples originated from the sea but also from the land such as Anatolia. The Sea Peoples have been credited for devastating the region and bringing nations and whole empires to an end. They pillaged and plundered and burned whole cities as they passed through.

Identified by Egyptian sources across multiple pharaohs, scholars have isolated but not entirely identified a total of ten tribes or groups of Sea Peoples who were said to have wreaked havoc in Egypt. Why Egypt? It was the center of wealth, power and civilization in the then economic world. It would have been an attractive location for anyone looking for new opportunities.

The Shardana

As scholars, we often find ourselves searching for clues in the most unlikely of places. We are talking about the Old Testament Bible. Outside of the archaeology and the Egyptian texts, the Bible “is considered” to be yet another source of literature which describes the enigmatic Sea Peoples.

In the world of academia, it has always been the general consensus that some of the Bible’s poetry predates its prose literature. For instance, the poetry came first, whether it was preserved orally or otherwise and eventually the prose stories were built around it. The same theory has been applied to the Song of Deborah (i.e., Judges 5) which scholars date to ca. 1100 BCE.

It is generally accepted that this poem preserves an Israelite battle against the Shardana (or Sherden), a war like group of Sea Peoples that eventually occupied the area of the Levant from around the 14th century BCE and later. This connection was made when scholars studying some of the archives found at Ugarit, located to the North of the battleground, discovered the name of a prince of a nearby Shardana colony dating to the 14th century BCE. His name was Zi-za-ru-wa or Si-sa-ru-wa, that is, Sisera (Zertal, 31). The very same name found in the poem of Judges 5; however, it should not be assumed that this is the same Sisera. The name could and would have been a common one.

5:19 The kings came and fought, Then the kings of Canaan fought In Taanach, by the waters of Megiddo; They took no spoils of silver. They fought from the heavens;

5:20 The stars from their courses fought against Sisera.

5:21 The torrent of Kishon swept them away, That ancient torrent, the torrent of Kishon.

Shifting back to the poem, it tells of a battle that occurred between Megiddo and Taanach. Archaeological Professor Adam Zertal had found evidence of a Shardana settlement just south of this location at el-Ahwat (Arabic for “the Walls”). This settlement dates to 1220-1170 BCE. After 1170 BCE, it had not been occupied since (Zertal, 26).

As mentioned earlier, the Shardana have been in and around the Levant for centuries and are also fairly well documented across multiple sources. We see evidence of their occupation in the general Near East as early as the Amarna Letters (i.e. EA No. 81, 122 and 123) dating to the 14th century BCE. Here they served as part of an Egyptian garrison in Byblos, where they provided their services to the mayor, Rib-Hadda. They served as personal guards for Ramesses II and fought alongside the pharaoh in his most memorable battle against the Hittites at Kadesh. The inscriptions of Merneptah and Ramesses III pit the Shardana against the pharaohs as part of the coalition of Sea Peoples invading Egypt. At approximately 1100 BCE, the Onomasticon of Amenemope lists them as occupying the Phoenician coast along the Eastern Mediterranean in the Levant. In almost every documented source, the Shardana were commonly depicted as hired mercenaries. In administration documents from the reign of Ramesses III, there is evidence for settlements, both land and goods intended for Shardana mercenaries ( D’Amato, Sea Peoples, 14).

Did the Song of Deborah mark the defeat of the Shardana, led by Sisera and either force them to evacuate el-Ahwat or disappear completely from the region? If this did mark the defeat of the Shardana from el-Ahwat, then can we date this poem to 1170 BCE? The orthographical (i.e., spelling) studies of Frank Moore Cross and David Noel Freedman to even the research of William Foxwell Albright place the style of poetry to no later than 1100 BCE (Cross, 3) and with a date of 1170 BCE for the actual battle, it would seem like a probable date of composition.

What of their origins? It is believed and generally accepted that the Shardana came from the island of Sardinia:

Men from southern Sardinia went off to Byblos and Ugarit, and eventually to Egypt, and it is unlikely that many of them returned home or wished to do so. In the eastern kingdoms they could enjoy the pleasures of urban life and at the same time be men of status and property with lands assigned them by their king; in return, they were obliged only to guard the palace during peacetime and to run in support of the fabled chariot forces on those rare occasions when the chariots gave battle (Drews, 218-219).

It would be the Mycenaeans and possibly the Cypriots that introduced the possibilities of a better lifestyle to Sardinian peoples. This in turn encouraged many to sail East for new opportunities.

On the coasts of Italy, which was equally primitive, Mycenaeans had established emporia at Scoglio del Tonno, on the Gulf of Taranto, and at Luni sul Mignone, in Etruria. For those “Tyrsenians” who lived nearby, these emporia must have advertised the possibilities that the lands to the east had to offer. The contact between eastern Mediterranean and Sardinia, and the easterners’ exploitation of Sardinian copper, has only recently been appreciated. But it now seems likely that in the thirteenth century most Sardinians who lived within a day’s walk of the Golfo di Cagliari would have seen the visitors’ ships, if not the visitors themselves, and would have been well aware of the discrepancy between their own condition and that of these peoples from the east (Drews, 218).

The earliest connection one can make of the Sherden with Sardinia comes from a 9th/8th-century BCE Phoenician stele inscription discovered from the ancient Sardinian city of Nora containing the word Srdn (D’Amato, Sea Peoples, 17). The archaeological evidence draws attention to similarities of Sherden in Egyptians depictions when compared with statue menhirs [1] discovered in southern Corsica and the many Nuragic bronze statuettes of warriors with similar horned helmets found in Sardinia. However, these statuettes were produced centuries after the original Sherden.

The Nuragic period of Sardinia starts at approximately 1600 BCE and ends shortly before the Phoenician occupation at 850 BCE (Dyson, 19). The Nuragic culture takes its name from the nuraghi (singular, nuraghe). The nuraghi are ancient constructions that dot the island of Sardinia which in the ancient Sardic language simply translates to “heap of stones.” The buildings are built of stone and vary in size.

Sometimes they are rounded, but most often they are irregular or wavy in design and have corralled roofs. They always contain curving corridors that connect the rooms, and the more developed structures even have staircases. More than 6,500 nuraghi have been found in Sardinia (Zertal, 26).

Its functions are largely unknown and scholarly opinions differ sharply. Regardless of its role in ancient Sardinian culture and society, similar structures have been found elsewhere in the Mediterranean region and to the East.

It has been proposed by archaeologist Adam Zertal that the same Sherden site of el-Ahwat was a Nuragic site:

After we had learned about the similarities between our site in Israel and nuragic architecture in Sardinia, I went to Sardinia for the first of several visits to consult with Professor Giovanni Ugas of the University of Cagliari, in the island’s capital.

[ … ]

As we studied the evidence, we grew more and more convinced that the inhabitants of el-Ahwat knew Sardinia well. Probably they—or their ancestors—had originated there (Zertal, 27).

Through a process of elimination, Zertal was able to conclude that the occupants of el-Ahwat were connected with Sardinia implying that these Sherden migrated to the East looking for opportunity and a new life.

Back to Lemnos

What did the Greeks say about Lemnos and the Lemnian inhabitants? The 5th century BCE historian, Thucydides tells us:

There is a small Chalcidian Greek element, but the majority of Pelasgians (descended from the Etruscans who once inhabited Lemnos and Athens), or else Bisaltians, Crestonians, or Edonians.

Thucydides The Peloponnesian War, IV.109

Even then, there seemed to have been an understanding that either Etruscans or another group from the Tyrrhenian region inhabited the island. The Etruscan language was a pre-Indo-European language. It is closely related to the Raetic language spoken in the Alps to the north of Etruria and likely on the islands of Corsica and Sardinia to the West of Etruria. It is unlike any other European language and stands on its own and while it influenced Latin, it was eventually superseded by it. Scholars continue to struggle with its decipherment, as a limited number of inscriptions have survived the test of time. The discovery of the Lemnos Stele implies one of two scenarios: (1) a group of Tyrrhenian speaking peoples migrated to the island sometime during the Late Bronze Age or (2) the Etruscans established a trading colony on the island during the Iron Age.

One thing is for certain, the language of the Lemnians was different from that of the Greeks and possibly Anatolians. [2] This was recognized as early as Homer:

“Come, love, let us to bed and take our joy, couched together. For Hephaestus is no longer here in the land, but has now gone, no doubt, to Lemnos, to visit the Sintians of savage speech.”

Homer, The Odyssey, viii. 290-294

Much like the Etruscan language, modern linguists have a limited library of Lemnian inscriptions to compare to and with.

So, do we have evidence of Shardana moving eastward for new opportunities. Who is to say that on the way, a small group occupied and eventually settled the island of Lemnos?

Another clue may be provided by the image portrayed on the stele itself. It seems to represent a soldier, holding both a shield and a spear, emphasizing the importance of being a warrior or at least, a soldier to their peoples. Honestly, this type of imagery is not unique and many cultures, including that of the Greeks, valued the same concepts.

Can we conclusively place the Shardana on Lemnos and say that the culture represented by them is a remnant of a Shardana colony? Unfortunately, no but as we continue to dig up more clues, with it, will come more answers.

Notes

[1] Statue menhirs are a type of carved standing stone found in Corsica, Sardinia, Italy and elsewhere in Europe dating from the European Neolithic period and later.

[2] The Mycenaean Greeks were familiar with the island and inhabitants of Lemnos. We find references to Lemnian woman or ra-mi-ni-ja in Linear B texts. Much of the material culture in LBA Lemnos showcase Mycenaean influence.

Sources

Bonfante, Larissa and Judith Swaddling. Etruscan Myths. Austin: University of Texas P, 2006.

Cross Jr., Frank Moore. David Noel Freedman. Studies in Ancient Yahwistic Poetry. 2nd ed. Grand Rapids: William B Eerdmans P Co., 1997.

D’Amato, Raffaele and Andrea Salimbeti. Sea Peoples of the Bronze Age Mediterranean c. 1400 BC – 1000 BC. Oxford: Osprey P, 2015.

D’Amato, Raffaele and Andrea Salimbeti. The Etruscans. Oxford: Osprey P, 2018.

Drews, Robert. The End of the Bronze Age: Changes in Warfare and the Catastrophe ca. 1200 B.C. Princeton: Princeton UP, 1995.

Dyson, Stephen L. and Robert J. Rowland, Jr. Archaeology and History in Sardinia From the Stone Age to the Middle Ages: Shepherds, Sailors, & Conquerors. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Museum, 2007.

Zertal, Adam. “Philistine Kin Found in Early Israel.” Biblical Archaeology Review, May/Jun 2002, 18+.