Forged by Sea and Stone: Exploring the Mysteries of Early Cycladic Culture

Featured Article

By Jess Nadeau

When Theseus departed for Crete to slay the Minotaur, his father left him with one message. Upon his return to Athens, he must raise the white sails of victory to signal his survival. Day after day, Aegeus waited, watching the waters from the cape. Alas, he spotted his son’s ship, and his heart soared until he noticed its sails remained a cheerless black. On board, Theseus was so taken by celebration that he neglected to raise the sails his father desperately needed to see. Aegeus did not wait for the ship’s return; he leapt from his high rock and plummeted to the sea. Theseus would go on to name the cerulean sea surrounding Greece, the Aegean, after his cherished earthly father and king of Athens.

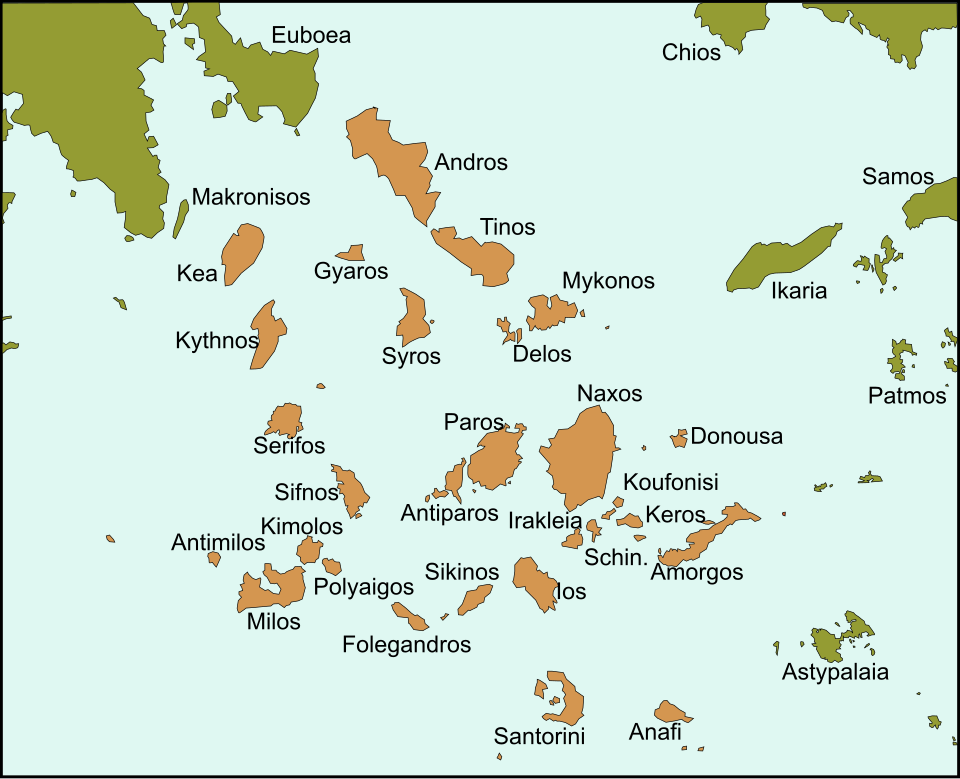

What lies in the vast Aegean beyond Greece is a myriad of islands. Crete had gained fame for its exceptionality, its mythical monster, and its vibrant culture. Yet, for others, more than 200, their history is shrouded by the influence of their successors. These are the Cycladic islands, a society of wanderers. They were rich in metal and stone, clever and resourceful on islands that may have supported little more than rock, shrub, and sand, and courageous, leaving their mainland homes behind to start anew. While much about Cycladic culture remains a mystery, what endures reveals a people forged by their own resilience and creativity, inhabiting a ring of islands that inspired even the gods themselves.

Allure of the Islands

As early as 5000 BCE, inhabitants of Asia Minor began migrating to the Cyclades. They likely brought with them seeds and livestock, resources needed that the islands could not offer. However, the islands did have something else to offer, something far more prosperous. Many of the Cycladic islands were abundant in copper, obsidian, lead, silver, and marble. Archaeological evidence suggests that the obsidian used by Neolithic mainland Greeks had been foraged in Melos prior to its inhabitation. As such, the islands were an alluring prospect, but not ideally hospitable. Still, they came anyway, with their animals, family, and whatever else their simple ships could carry, and began building. Early settlements would have been small, comprising farmers and fishermen, who were the primary means of sustaining life.

The archaeological timeline of the Cyclades is split into three periods, taking place during the Early Bronze Age and into the Middle Bronze Age, based on pottery style, graves, and figurines: Early Cycladic I (3200-2800 BCE), Early Cycladic II (2800-2300 BCE), and Early Cycladic III (2300-2000 BCE). Historically, Cycladic culture began with graves of marble slabs on Melos and Naxos. Small communities eventually sprawled into larger urban areas. Unbaked clay structures sat atop stone foundations. Wheat, barley, olives, and grapes were thriving against all odds. Sheep, pigs, cattle, deer, and fish like tuna and perch filled their hungry bellies. They wove textiles to clothe their bodies, adorned with jewels of silver and copper, and crafted darkened, burnished vessels decorated with incised spirals and ships or, later, painted white. Copious amounts of marble created jars, bowls, beakers, and pans for cooking, quite similar in style to those of the mainland Greeks and Anatolia. Tools were shaped from bone, shells, and obsidian. Marble slabs used for the burial of inhabitants also fortified their land. As a seafaring society, they frequently relied on trade. Geographically advantageous, Cycladic islanders were able to move about the Aegean freely, trading with Mycenae, Crete, and Anatolia.

It is through the burgeoning of trade that the Cyclades prospered. Mineral-rich resources and stone allowed them to barter in a way that no other could. Transformations of multicultural beginnings additionally contributed to their memorable and unique style of craftsmanship. They were skilled metallurgists, artisans, and administrators. Most notable was their specialized use of white marble to fashion highly stylized figurines of an almost ethereal composition that glimmered in the sunlight.

The earliest Cycladic figurines were Neolithic robust female figures, not so different from the Paleolithic Venus figure. Though stylistic, Cycladic figures display widened hips and arms that rest on the chest. Early Cycladic I figurines were violin-shaped with elongated heads, small protrusions as arms, and no legs, quite similar to other figurines located around the Mediterranean. Figurines in Cyprus, during the Early and Middle Bronze Age, also had this unusual style of portraying the female body, something evidently widespread for a considerable amount of time, including on the Greek mainland.

At the beginning of the Early Cycladic II period, figurines start to transition to a slightly more naturalistic style. Facial features remain mostly schematic, while body postures become noticeably expressive. Seated figures play the harp or clutched ceremonial cups; figures are layered atop one another in familial embrace; hunters, warriors, and various species of animals were vibrantly colored, used and repaired several times, eventually retiring to their eternal homes alongside their deceased owners.

Distinctly Cycladic, these figurines are paramount in understanding Aegean culture. Since formal writing is lacking, reconstructing the society relies heavily on archaeological discoveries like these, found in specific contexts, along with their trade histories and future influences. As such, the figurines suggest some measure of hierarchy and personal significance, as many were found amongst graves of the wealthy and served a lifetime purpose. More importantly, however, they shed light on lively communal and ceremonial activities as well as a likely religion.

Spirituality and the Female Figure

When considering common themes found throughout the ancient world, female figures accentuating the belly or breast usually indicate the presence of a mother goddess, a symbol of life, abundance, and fertility. In some cases, figurines can represent elders or ritual specialists, but this does not necessarily fit with the Cycladic figures found. Speculation points to figures found in graves as concubines or slaves sacrificed for service in the afterlife, comparable to the ushabti figurines of ancient Egypt, meant to serve as servants and laborers to the deceased. Or perhaps, they were merely playthings for children; yet, this, too, does not explain why they were repaired and repainted numerous times and buried with adults.

It is more likely, then, that these figurines, plentiful in female form early on, represented something similar to the female-centered religions of other societies. Keeping in mind that these people would have migrated from Anatolia and the Greek mainland, evident in similarities in wares and attested to by ancient historians. Both Herodotus and Thucydides referred to them as Carians, purported to have migrated from Anatolia, and settled in the Aegean. As such, they would have retained some of their native traditions, building upon them.

Early female-centered religions can be found in ancient Sumerian, Akkadian, Babylonian, Egyptian, and, as expected, Minoan society. As life-bearing goddesses, they were connected to nature and the endless cycles of life, death, and agriculture. Intrinsically, therefore, the role of midwife would have been of the utmost importance, having abilities akin to the goddess herself, aiding the community through life’s transitions. It is possible that the figurines could be representative of the midwife. Even so, there would naturally need to be a link between the midwife role and something divine, as there would be with ritual specialists and elders. Thus, through the understanding of ancient societies and their principal gods, who often wove the threads of human fate, the cosmos, and demanded offerings and prayer, the purpose of the figurines may be realized.

During the Early Cycladic II period, particularly on the islands of Keros and Syros, life-sized marble figures bore the same resemblance to the miniatures found throughout the islands. The location where these giant figures had been found on Kavos, Keros, shows clear evidence of ritual activity, deemed a sanctuary. What is interesting about this site is that it appears to be a dumping ground of sorts, with scattered remains of various small figures, some of which appeared to have been methodically cut at the neck, chest, waist, knees, and so on. The fragments were then placed with the deceased for unknown reasons. It has been speculated that the supposed wounds of the figure were to replicate the wounds of the dead.

As for other remains found on the site, they may have been sacred charms or included in ritual or festival activities. All the more compelling is the Dhaskalio pyramid. Shaped by wind and waves, the naturally occurring pyramid-shaped promontory had been altered into a step pyramid, an ingenious monument to still rather mysterious religious rites. Whatever occurred on Kavos would have been grand in every sense of the word. Nonetheless, it’s vital to bridge beyond the female figure, because during the whole of the second period of the early Cycladic, figures of small and large stature were male and female, fluid in their portrayals, like the harp player and the hunter.

What these figures reveal in the context in which they are found is a religion that possibly evolved to polytheism. As such, several aspects stand out: the female mother goddess, the hunter, the bard, and the ambiguously gendered. The ambiguously gendered figures, displaying male and female characteristics, may be indicative of ritual specialists or beliefs and practices that expressed themselves in both masculine and feminine ways; in other words, they were seen as male and female, but neither female nor male as defined, a third gender. This concept would later be found in the Greek Hermaphroditus, whose father was Hermes, a god known as an intermediary between worlds. It is also found in ancient Mesopotamia, through the ambiguously gendered gala that served the goddess of war, love, and fertility, Inanna (Ishtar).

Further, the musician as well as the hunter may be embodiments of festival activities, which historically involve deities and the expression of a shared cultural identity. Some have speculated that these prominent figures, specifically the female, were early counterparts to Artemis of Ephesus, Anatolia, revered as a mother goddess of fertility. The similarities between early conceptions of Artemis and even Apollo are compelling, but so little is certain about the people of the Cyclades. Additionally, as time went on into the later part of the Middle Bronze Age and throughout the Late Bronze Age, the islands became increasingly like their influential neighbors, the Minoans, in culture and religion, blurring the lines between the two. Though there is still much to be said when considering the world around them and what evolved thereafter.

The Birthplace of Gods and Lovers

During the Early Cycladic III Period, which encompassed the greater part of the Middle Bronze Age, Cycladic society began increasing in size and relative sophistication. On larger islands, populations moved to fortified harbors. Building projects expanded, as well as trade opportunities. Pottery displayed new designs, abstract motifs painted white with geometric, floral, or spiral designs. Life-size figures glowed against the sun in sanctuaries and shrines. It was inevitable that the Aegean cultures would merge.

The majority of the islands, mainly to the south, adopted Minoan culture, while some of the northeastern islands adopted some but not transformational aspects of western Anatolian culture and technology. According to Thucydides, King Minos had conquered, expelled what he referred to as barbaric and piratical Carian malefactors, and colonized the islands. Herodotus claimed that the islanders served as part of Minos’s navy, then called Legeles, until some were expelled and others assimilated into Minoan culture. Though, it remains unclear if any of this really occurred or to what extent, the Minoans did appear to have ample sway in redefining the Cyclades. This does suggest that there was a degree of colonization, but perhaps it was more to do with migration, trade, and the introduction of beneficial technologies. In any case, by the Late Bronze Age, the cultures were virtually indistinguishable and often seen as a whole.

When Thera erupted between 1650 and 1550 BCE, it caused widespread destruction and instability, opening the region to new sovereigns, the Mycenaeans. By 1400 BCE, they completely dominated the Aegean, but the victory was short lived. By 1200 BCE, their influence diminished along with the security of the Mediterranean world. The Bronze Age collapse left settlements of the islands abandoned, destroyed, and overrun with piratical groups for several hundred years. Between 800 and 700 BCE, the Archaic Greeks salvaged the vestiges of a once brilliant society. The pirates would continue to be a problem or an advantage to those who could utilize them. Be that as it may, several islands were given new life. Myths and deities sprang from their beaches, bestowing bounties of divinity and devotion, reimagining old and forgotten traditions.

The name of the islands, as it is known today, comes from the Greek word kylos, meaning circle. It was given this name because the islands surround Delos, an island of great mythological significance; from 700 BCE onward, Delos served as a sanctuary to Apollo and Artemis. According to Hesiod and a Homeric hymn, the island gave refuge to a laboring Leto when all other places had failed her. Leto, the daughter of Coeus and Phoebe, was one of the Titanides (female Titans), a goddess of motherhood and protectress of children. As one of many of Zeus’s affairs, she was banished by Hera from giving birth; no land that sees the light of day would receive her. She wandered Greece, only to be faced with indifference. Finally, she took to the sea, encountering two floating rocks that lived beneath and above the waves, unrecognizable to gods or mortals as seeing the light of day. The rocks spoke and offered her shelter and solace.

Exhausted and nearing delivery, Leto stumbled onto Delos, steadying herself on a nearby palm tree, where she then gave birth to the god of music and prophecy, Apollo. On the other island, Ortygia, she birthed the huntress, Artemis. Such a miraculous event it was that swans began circling the island of Delos, and a gleaming light shone so bright that it brought the mightiest of gods and all the neighboring islands from their homes to bear witness. The islands remained as a protective fortress around the sacred island. Some myths claim that Artemis was born first, aiding her mother in the birth of Apollo. Other legends of the island suggest that an enraged Poseidon shattered the mountains of Greece and sent them flying into the Aegean, forming the islands, or that he transformed sea nymphs into the islands. Either way, Delos would become the center of Apollo and Artemis worship, fitting for its past.

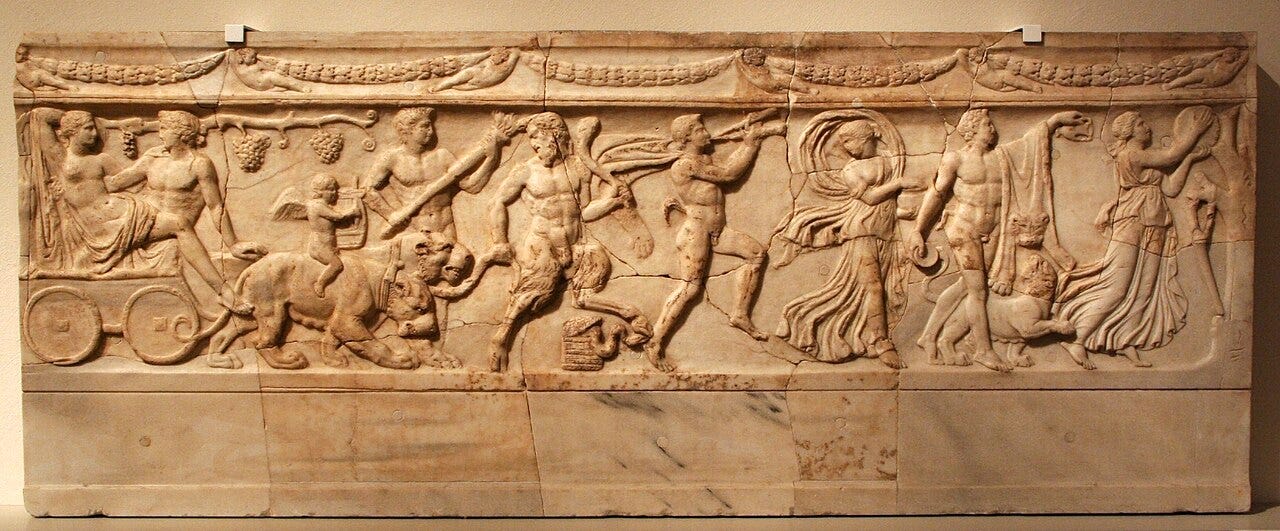

On Naxos, there were temples to Apollo, Demeter, and Dionysus. It was believed that the god of wine and pleasure was born here amongst its flourishing vineyards. Here, his festivals were famous throughout the Greek world, and his temple was second to Thebes. It is also here that the god wed Ariadne, the unfortunate victim of fickle Theseus. As the hero headed home to Athens, he stopped by the island, where he impenitently abandoned Ariadne, who had sacrificed her home and family to help him. Despairingly, she watched as his ship sailed away into nothing more than a dot on the horizon. Her woes soon faded as the wilderness behind her began to stir, and from it emerged the beautiful and androgynous Dionysus, along with his spirited satyrs and maenads. Welcoming her into his arms, he wooed her with dazzling gifts and wine until her heart requited his love.

Another celebrated hero of legends also had ties to the islands. The princess, Danae, spent much of her youth in lonesome solitude at the hands of her father, who believed her future son would one day be his demise. This imprisonment, however, did not stop Zeus from shining down on her in a show of glittering, golden ambience. Danae attempted to hide her child with Zeus once he was born, but her father was quick in his perpetual paranoia. Heaving her and the child into a chest, he sent them adrift at sea. Floating atop tumultuous waters, Danae clung to her son until they washed up on the shores of Seriphos. The humble fisherman and king’s brother, Dictys, gave them refuge for a time. Perseus was the child’s name, and later into adulthood, the cruel king of the island, Polydectes, would send him on an impossible quest to be rid of him and take reluctant Danae as his wife. Perseus left at the will of the king to retrieve the head of the frightful Medusa. His unanticipated return left the king and his court turned to stone and his mother free from the pitiless ruler. Later, in Larissa, a stray discus thrown by Perseus during an athletic game struck and killed his unsuspecting grandfather, King Acrisius, as he watched on as a spectator, fulfilling the dreaded prophecy.

A Culture that Continues to Inspire

The Greeks, like many others, had an imaginative way of retelling their past. Histories became myths, and heroes became legends and demigods. What is known about the Minoan culture attests to their mythification. Though the Cyclades still elude archaeologists, their past predates that of Crete and the mainland Mycenaeans, and they are one of the oldest cultural sources in all of Europe. The sanctuary at Kavos was also one of the earliest in maritime history. After Greece took over the islands, its history became intertwined with the spiritual and political spheres. At times, they were nearly conquered by foreigners or forced to choose sides amidst a feuding Athens and Sparta.

By the 2nd century BCE, the Cyclades were under the control of the Ptolemies. By 88 BCE, Delos was attacked, stability waned, and the islands would eventually evolve into safe havens for pirates or places of exile for criminals. During Roman times, many of the islands once inhabited were barren of civilization, even from the pirates. On Gyaros, the extremities of isolation and lack of resources were a harsh punishment, so few would have survived. Pirates exerted their control over the Aegean throughout the eras, rampant during their golden age.

What little may have been left of the original inhabitants disappeared with time and wavering alliances. Still, the Cyclades may have laid the foundations for later beliefs. Their hunters and mother goddess became Artemis, their musicians became Apollo, and their festive traditions became Dionysus. Their glistening marble statues and figurines may have even inspired the mythical light that shone down, gathering the gods and islands during Apollo’s birth. Certainly, they were more than their memorable marble figures; they were a people who created something extraordinary out of seemingly nothing. Though thousands of years have passed, the islanders continue to tell legends of old and new, and the unique style and physique of ancient figurines continue to inspire modern, abstract artists from around the world. An homage, perhaps, to a people whose lives are an enigma that may never be fully deciphered.

Featured image: Keros island with Cycladic figurines.

References

Cartwright, M. 2012. Cyclades. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Cyclades/

MacGillivray, J.A. 2024. Who Were the Early Cycladic Figurines? The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Available at: https://www.metmuseum.org/perspectives/cycladic-figures

Powell, B.B. 2015. Classical Myth. Pearson Education, Inc.

Herodotus, Translated by Holland, T. 2015. The Histories. Penguin Books.

Thucydides, Translated by Crawley, R. History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 1. Available at: https://classics.mit.edu/Thucydides/pelopwar.1.first.html

Theoi Greek Mythology. Leto. Available at: https://www.theoi.com/Titan/TitanisLeto.html