Iconoclasm: The Art of Destruction

Guest Article

By Leslie Ivings

When we hear the word iconoclasm today, many think of statues dragged from their pedestals, of stained glass smashed from church windows, or of portraits of political leaders daubed with paint. The word surfaces whenever societies confront their past by targeting its most visible symbols. Yet its meaning is older and deeper than these modern scenes suggest. Derived from the Greek eikon (image) and klan (to break), iconoclasm literally means “image-breaking.” At first sight it appears to be a straightforward act of destruction. But behind the breaking lies something more significant. Images are never neutral. They embody memory, power, and belief. To attack them is to contest what they stand for, to challenge those who revere them, and to redefine the future.

The Christian world was the first to give the word its sharpest edge. Christians had inherited the biblical suspicion of idols. The commandment in Exodus against “graven images” warned that the worship of anything made by human hands was a form of betrayal. At the same time, Christianity proclaimed the Incarnation, the conviction that God had taken on visible human form in Jesus Christ. How then was a believer to reconcile a rejection of idolatry with the reality of the divine made flesh? John of Damascus, one of the most articulate defenders of sacred images, once asked: “When the Invisible One becomes visible to flesh, you may then draw his likeness. When He who is bodiless and formless, immeasurable in the boundlessness of His own nature, existing in the form of God, takes on the form of a servant, then you may draw His likeness, and show it to anyone who is willing to contemplate it.” For John and others, to ban the image of Christ was in effect to deny the Incarnation itself. But for their opponents, images represented a dangerous slide into idolatry, a form of worship of the creature rather than the Creator.

It was in the Byzantine Empire that this controversy erupted with full force. Byzantium was saturated with images. Icons of Christ, the Virgin, and the saints adorned churches, palaces, and private homes. They were objects of devotion, kissed, venerated, and treated as mediators of divine power. Around 726, however, Emperor Leo III ordered the removal of a famous icon of Christ from the Chalke Gate of the imperial palace in Constantinople. His motives remain debated. Some suggest that defeats against the advancing armies of Islam, a religion whose mosques avoided figural representation, persuaded him that God’s anger lay heavy upon Byzantium. Others see Leo’s action as part of an attempt to assert imperial authority over the church and its powerful monastic communities.

Whatever the precise reasons, his act unleashed a century of turmoil. Icons were removed from churches, replaced with simple crosses. The production of new icons was forbidden. Defenders of the practice, especially monks, faced exile, persecution, or worse. John of Damascus, living beyond Byzantine borders under Muslim rule, wrote his treatises in defense of icons, declaring that “the honor paid to the image passes to the prototype.” His writings became foundational for the iconophile position, asserting that images were not idols but visible witnesses to the truth of the Incarnation.

The first wave of iconoclasm lasted until 787, when Empress Irene convened the Second Council of Nicaea. The bishops gathered there made a crucial distinction between latreia (worship) and proskynesis (veneration). Worship, they insisted, was due to God alone, but icons could be venerated as signs pointing beyond themselves. “The honor rendered to the image,” they declared, “ascends to the prototype.” With this, icons were formally restored to Byzantine churches.

Peace, however, proved fleeting. In 815, under Leo V, iconoclasm was revived, ushering in a second and often more aggressive wave of suppression. Churches were stripped once again, bishops and monks who resisted were harassed or deposed, and the debate deepened. It was not until 843, under the regency of Empress Theodora, that icons were definitively restored. This event, known as the Triumph of Orthodoxy, is still commemorated in the Eastern Orthodox Church every year on the first Sunday of Lent. The legacy of the controversy was profound. Out of the struggle came a theology of images that remains central to Orthodox Christianity, one that sees icons not as mere decoration but as sacramental windows into the divine.

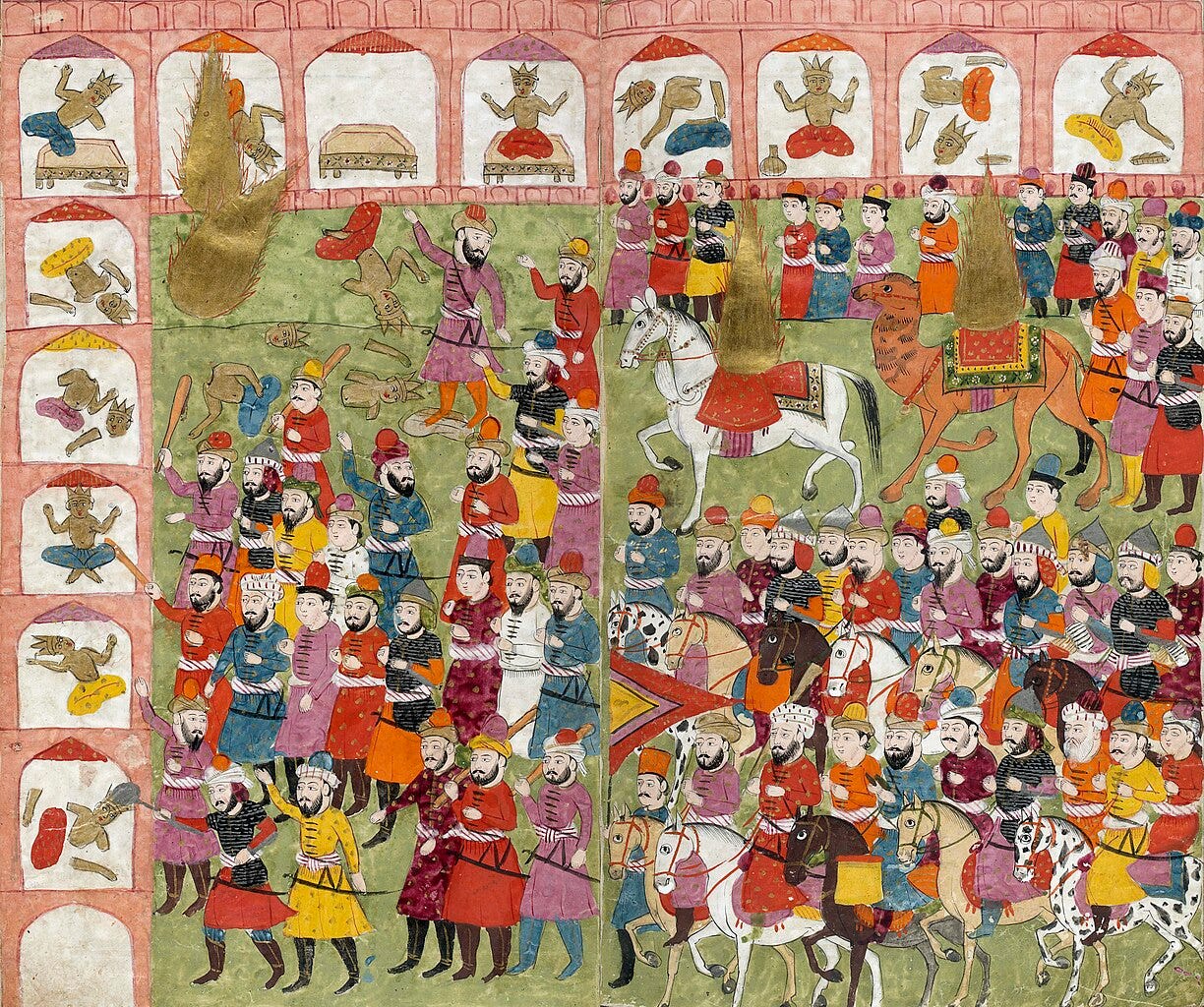

Although Byzantium gave iconoclasm its defining episode, the phenomenon was not confined to the Christian East. The Protestant Reformation in sixteenth-century Europe unleashed its own wave of iconoclasm. Reformers such as Huldrych Zwingli in Zurich and John Calvin in Geneva denounced what they saw as the idolatry of Catholic imagery. Their followers acted decisively. In Zurich in 1523, reformers stripped churches bare of paintings and sculptures. In Geneva, stained glass was smashed, statues toppled, and church interiors whitewashed to eradicate every trace of what was judged superstition.

In England, the waves of iconoclasm were equally devastating. Under Henry VIII, the Dissolution of the Monasteries not only closed religious houses but also saw the destruction of countless images, relics, and works of art. Under the Puritans in the seventeenth century, parish churches lost medieval wall paintings and stained glass that had survived the initial upheavals. Canterbury Cathedral’s magnificent glass was shattered, and wooden carvings were hacked apart. For the reformers, such violence was a theological necessity. Salvation came through Scripture and faith alone, not through the intercession of saints or the veneration of images. Yet the physical legacy was dramatic. The aesthetic of many Protestant churches, with their white walls and stripped interiors, continues to testify to the power of iconoclasm long after the passion that drove it has cooled.

Islam too has wrestled with questions of images. The Qur’an itself does not prohibit all images, but traditions developed around avoiding figural representation in mosques and religious contexts. This gave rise to the dazzling achievements of Islamic calligraphy, geometric pattern, and arabesque, art forms that sought to reflect the infinite without relying on human or animal figures. Yet across the Islamic world attitudes varied. Persian miniatures depicted scenes from epic poetry, Mughal artists painted portraits of emperors, and Ottoman court ateliers produced figurative works. The tradition was therefore more complex than an absolute prohibition.

In modern times, however, reformist movements emphasized stricter aniconism. Wahhabism, originating in eighteenth-century Arabia, condemned images and sought to purify Islam of what it saw as corrupt practices. In 2001 the Taliban destroyed the colossal Bamiyan Buddhas in Afghanistan, statues that had stood for over a thousand years. The act was justified in religious terms but was also a political gesture, an assertion of control and a challenge to global cultural authority. Iconoclasm here was not only about religion but also about power.

Political and revolutionary iconoclasm has been a recurring feature of modern history. In the French Revolution of 1789, revolutionaries toppled statues of kings, desecrated royal tombs at Saint-Denis, and melted down church bells to make cannon. These acts were not mere vandalism but deliberate attempts to erase monarchy and clerical privilege from the symbolic landscape. In the Soviet Union, religious imagery was suppressed, churches converted to secular use, and monuments to czars destroyed, only for their places to be filled by statues of Lenin and Stalin. Old icons were replaced by new ones, the cult of saints displaced by the cult of the leader.

Our own age is not immune. In the United States, debates over Confederate monuments have divided communities, with some seeing their removal as a necessary repudiation of racism, while others view it as erasure of history. In South Africa, the Rhodes Must Fall movement began in 2015 with the toppling of a statue of Cecil Rhodes at the University of Cape Town. In Britain, statues of slave traders and imperial figures have been defaced, removed, or contextualized with new plaques. These acts are iconoclastic in the literal sense, but they are also deeply political. They raise questions about what kind of history we wish to celebrate in public spaces, and whose memories are honored. Although the wanton destruction of any monument decries more a society that wants to forget and that those very altruistic actions of conscience may indeed have deeper historical consequences in the long run. Whatever can be said of Iconoclasm, it has always been divisive whether in the past or the present.

The paradox of iconoclasm is that it rarely succeeds in erasing memory. Instead, it often creates new memories. Empty niches in cathedrals, shattered faces on medieval statues, and vacant plinths where monuments once stood bear witness to absence as eloquently as presence. The very act of destruction can itself become iconic. Photographs of Saddam Hussein’s statue being pulled down in Baghdad in 2003, or of protesters daubing paint on public monuments, have become images that circulate globally. In this way, iconoclasm generates its own imagery, embedding itself in the cultural record.

The persistence of iconoclasm through history raises the question of why images matter so much. The historian David Freedberg argued that pictures provoke strong responses precisely because they are never inert. They draw emotion, reverence, anger, and fear. To destroy them is to acknowledge their potency. Iconoclasm is therefore not merely destruction but a confession of the power of images to shape human lives.

What, then, is iconoclasm? It is not simply the breaking of objects but the remaking of meaning. It is a mirror of society, reflecting its deepest anxieties and aspirations. The Byzantine emperors who tore down icons believed they were defending purity of worship. The Protestant reformers who smashed stained glass saw themselves as restoring the authority of Scripture. The revolutionaries who toppled statues, and the activists who spray-painted monuments, believed they were reshaping history itself. Iconoclasm has always been about more than images. It has been about who we are, what we remember, and what kind of future we wish to inhabit.

In that sense, iconoclasm is never only about the past. It is always also about the future. And most notably a future that can end up being or shattering than any lost record of the past.

Leslie Ivings is the author of Byzantine Emperor Constantine V, Pen & Sword (2025)

Constantine V - warrior, reformer, and one of Byzantium’s most formidable emperors. A brilliant general who crushed the Arab advance, strengthened the crumbling empire, and won the loyalty of his soldiers long after his death.

But history has not been kind. A fierce iconoclast, hated by the church and smeared by monastic chroniclers, he was branded Copronymos (“the dung-named”), compared to a sorcerer - even the Antichrist.

Married three times, politically astute, and as influential in theology as he was on the battlefield, Constantine’s legacy rivals Justinian himself. Yet unlike Justinian, he died not in splendour, but leading his army on campaign in Bulgaria.

Listen to Leslie Ivings discuss his book on our podcast:

The Dung Emperor: Constantine V

Petros Koutoupis sits down with historian and author, Leslie Ivings, to discuss his latest publication: Byzantine Emperor Constantine V, 'the Dung-named': General, Patriarch, Iconoclast, Reformer. Who was Constantine V, what great things did he accomplish during his reign and why were the Byzantine chroniclers harsh with his legacy? We will answer these…

Featured image: The Destruction of icons in Zurich 1524. (Public Domain)

References

Averil Cameron, The Byzantines (Oxford University Press, 2006)

Leslie Brubaker and John Haldon, Byzantium in the Iconoclast Era, c. 680–850: A History (Cambridge University Press, 2001)

John of Damascus, On the Divine Images, trans. D. Anderson (St Vladimir’s Seminary Press, 1980)

Carlos Eire, War Against the Idols: The Reformation of Worship from Erasmus to Calvin (Cambridge University Press, 1986)

David Freedberg, The Power of Images: Studies in the History and Theory of Response (University of Chicago Press, 1989)

Patrick J. Geary, Living with the Dead in the Middle Ages (Cornell University Press, 1994)

Finbarr Barry Flood, Objects of Translation: Material Culture and Medieval “Hindu-Muslim” Encounter (Princeton University Press, 2009)

James E. Young, The Stages of Memory: Reflections on Memorial Art, Loss, and the Spaces Between (University of Massachusetts Press, 2016)