Shepherd Kings of the Nile: Unraveling the Historical and Biblical Role of the Hyksos

Featured Article

By Jess Nadeau

At the beginning of Egypt’s 12th Dynasty, Pharaoh Amenemhat I established a settlement in the far northern region of the Delta, allowing ease of access to the Mediterranean as well as Semitic lands to the east. He called this place Avaris. Expectedly, the settlement flourished as a trading center, bringing in an influx of migrants. Those who had come to Avaris to start anew thrived, acquiring wealth and prestige throughout the 13th Dynasty.

Nearing the end of the Middle Kingdom, power struggles arose, droughts and famine took hold, and new alliances were made. Suddenly, the people of Avaris were far more powerful than they had ever anticipated. For a little over 100 years, they ruled Egypt and, in that time, were given their name, the Hyksos or Heqau-Khasut, Rulers of Foreign Lands. Yet, for all they were known for, they remained a people long shrouded in mystery. Just as quickly as they arrived, they vanished, and those who came after them only deepened their enigmatic allure.

The Age of the Hyksos

The Second Intermediate Period, spanning roughly from 1782 to 1570 BCE, comprised the 15th, 16th, and 17th Dynasties. Like all intermediate periods, this one is marked by a fragmented, decentralized kingdom: a transition of power in Lower Egypt to the Hyksos, native Egyptians at Thebes, and the Nubians in Upper Egypt. The reason this period is so centered on the Hyksos is due to swift changes in leadership that introduced a new group of people into the dominant political sphere, ones that inevitably set a precedent, altering the fabric of Egyptian life thereafter.

In all manners of custom, the Hyksos admired and adhered. They spoke the language of the people, added Egyptian names to their titulary, and honored native Egyptian tradition and religion. Their gods were identified with Egyptian deities, rather than replacing them. Notably, the Hyksos introduced new agricultural and military concepts that worked to Egypt’s advantage: the chariot and composite bow, just to name a few. The shifting powers of a divided Egypt also appeared to have maintained cordiality: trading and interacting between Avaris, Thebes, and Kush was frequent and saw little issue during this period.

Still, despite an outwardly amicable relationship between existing powers, history did not favor the Hyksos. Later historians, like Manetho, a 3rd-century Egyptian Priest, depicted the Hyksos as savage, invading oppressors who burned cities to ash, plundered, and desecrated holy temples. But archaeological evidence and records paint a very different picture. Sometime during the late 17th Dynasty, the reigning Hyksos pharaoh Apepi sent word to Seqenenra Taa (Ta’O) of Thebes, a formal complaint about a hippopotamus pool located in the east of the city that kept him awake at all hours of the day and night. Taken as an insult, Ta’O attacked Avaris, but a blow to the head from a few axes sent him to an early grave.

Petty quarrels escalated into vengeful plots; Theban powers seized the opportunity to rid themselves of foreign leaders. Kamose, son of Ta’O, launched his warships up the Nile, devastating Avaris. For the next three years, he campaigned multiple attacks until he finally captured Memphis. His successor, Ahmose I, after numerous attempts, finally destroyed Avaris and Khamudi, the last Hyksos pharaoh, was overthrown. Ahmose reclaimed Egypt, driving out the alleged invaders, and thus marking the end of the Second Intermediate Period and the beginning of the New Kingdom. All those who survived the brutality of expulsion fled to Syria-Palestine.

Who Were the Hyksos?

Theories as to who the Hyksos truly were have never ceased to arouse intrigue. One such theory had suggested that they were refugees from an Aryan Invasion, but this has since been dismissed. What we do know is that the Egyptians referred to them as Asiatic, a term used for people located east of Egypt from the Levant to Mesopotamia. A widely accepted theory suggests that they traveled through land routes from Syria-Palestine to Avaris, and as history tells, established a prominent position of power.

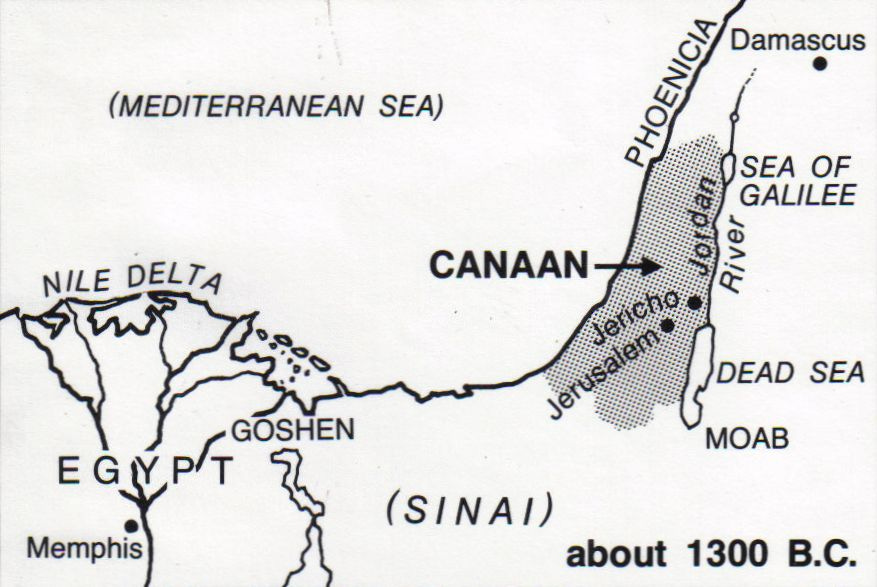

Archaeological evidence at Avaris reveals a port city reminiscent of Near Eastern architecture, style, and artifacts. Additionally, the names and language of all the Hyksos rulers were Semitic, specifically Western Semitic or Canaanitic. The region of ancient Canaan was commonly known as the Levant, an area that spanned the eastern shores of the Mediterranean. More specifically, the area associated with West Semitic land was Syria-Palestine. On a 17th Dynasty stela, Kamose refers to Apepi as Chieftain of Retjenu, a region later known as Khor, an area that encompassed most of Syria and home to Canaanites.

Aside from king’s lists and artifacts, much of what we have heard of the Hyksos comes from Manetho. However, his writings on the Hyksos, information he claimed to have received from New Kingdom scribes, are long gone, so everything we currently have available is based on 1st century AD Jewish-Roman Historian Flavius Josephus’ work Contra Apionem (Against Apion). According to Josephus, Manetho referred to them as Phoenician, a Greek term used to describe the people of the Levant.

Indeed, Manetho was right about their place of origin, though his descriptions of their dominion over Egypt have been heavily criticized. There is no known evidence to suggest the Hyksos carried out any sort of unprovoked destructive campaigns. Further evidence of any assemblages of strongholds at Avaris or Memphis is also absent; in other words, the cities were ill-prepared for conflict. The likely reason the Hyksos were painted in such a negative light may have more to do with propaganda, a strategy aimed at preventing foreign power from taking over Egypt in the future.

All things considered, there are still many questions left unanswered. We do not know much about their previous statuses, whether they were rulers of their lands, or if all the people of Avaris migrated from the same location. We only know what little the Hyksos rulers and long-lost histories have provided. Perhaps their ambiguity gives reason for the asserted associations with biblical texts. After all, they are quite similar in origin and departure to the Israelites, and the internet has no shortage of theories as to whether or not the two are one and the same, much of which is inspired by Josephus himself.

A Lasting Relationship to Biblical Israelites

The apparent relationship between biblical Israelites and the Hyksos appears with the arrival of Jacob and his family into Egypt. After a drought had swept over Canaan, Jacob sent his sons to Egypt in search of grain, but soon ran into their estranged brother, Joseph, the same brother they had sold into slavery years prior. Joseph, despite what his brothers had done, was welcoming. Having since elevated his status through noble service, the Lord rewarded him. His impeccable talents drew the attention of the pharaoh, and not long after, he was appointed as Viceroy, second in command. Joseph invited the family to stay, helping them to find land to settle. That land, located in the eastern Nile Delta, was known as Goshen.

Several things about this story would seem to connect to the Hyksos. First being the location, Goshen. Both Goshen and Avaris were said to be located in or around the Wadi Tumilat, the area east of the Nile Delta, and both were said to have a predominant Semitic population. And, at least according to some biblical researchers, the specific details of Joseph’s life would potentially align with the Middle Kingdom and Second Intermediate Period. Joseph was said to have shaved his beard upon meeting the pharaoh, which may suggest a native Egyptian pharaoh – unlike Semitic peoples, natural beards were unhygienic to the Egyptians; any beards worn were symbolic and false. It is also known that Joseph wed a native Egyptian woman who carried a name known to have existed during the Middle Kingdom, Asenath. What’s more, there were droughts and a great famine that occurred at the end of the Middle Kingdom.

In dating all of this, biblical researchers have used chronologies that work back from the Exodus to the arrival of Jacob and his family, placing Joseph during the late 12th Dynasty, specifically during the reign of Amenemhat III and Sobekhotep I in the early 13th Dynasty. Amenemhat just so happened to have a Vizier whose name, Anku (Ankh meaning life), may be a direct nod to Joseph’s given name, Zaphnathpaaneah, He Who is Called the One Who Lives. Similar to Joseph’s duties, this Vizier was an overseer of agricultural projects and grain. One of those projects was a canal appropriately named Bahr Jussef or Joseph Canal. In addition, parts of Avaris were later rebuilt upon and named Pi-Ramesses or Ramesses, after the 19th Dynasty pharaoh Ramesses II, another purported name for Goshen.

When considering the famed Exodus, there are a few things worth exploring. Assuming the above timelines are correct, the Israelites may have settled in Egypt during the Middle Kingdom, and were enslaved by a resentful pharaoh during the New Kingdom, thus leading to their passage to freedom across the Red Sea. Taking into account a modified, realistic approach to the generational gap between Solomon and Moses -12 generations with 25 years allotted to each generation - biblical researchers have been able to place the oppression of Israelites during the reign of Seti I and the Exodus during the reign of Ramesses II, supporting popular theories as to when the Exodus occurred.

So, how does any of this connect to the Hyksos? Well, the time of their estimated arrival seems to correlate with migrations to Avaris, though the name of each settlement varies. The Hyksos were expelled from Egypt, and the Israelites fled oppression and slavery. In both cases, the act of fleeing represents freedom and new beginnings. Josephus was adamant in his claims that the Hyksos were the Israelites, that they journeyed through the wilderness and founded Judea, and it was called Jerusalem. Modern scholars have also suggested that the expulsion of the Hyksos inspired the story of Exodus.

Going a bit further back, according to the Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology, the term Hyksos was first seen in the 12th Dynasty, which, based on their chronologies, may coincide with Abraham’s pilgrimage across the Euphrates into Egypt. Though Jacob marks the beginning of the migration of Israelites into Egypt, Abraham arrived some 200 years prior. If Jacob arrived towards the end of the 12th Dynasty, this timeline could work if Abraham were to arrive at the beginning of the dynasty – the 12th Dynasty lasted between 190 to 213 years, depending on the source. As noted earlier, the Hyksos seemed to have arrived around this time as well, the 12th to 13th Dynasties. If plausible, there would be some overlap in the timeline of the Hyksos, Jacob, and Abraham.

Nevertheless, certain facts must be considered: the Hyksos and the Israelites did not have these names naturally. It is likely the Hyksos may have called themselves Canaanites or something similar, given their heritage. We do know that during their time in Egypt, the Israelites were known by the Egyptians as Hebrew, a word that appears during the New Kingdom and is derived from the Egyptian word Apiru (Habiru or Hapiru). Habiru was a name given as a designation for those who were outsiders, nomadic or other, who were low-status laborers, providing various services for pay. The obvious must also be considered: the Hyksos were rulers, the Israelites were said to be slaves, and the rebuilding of Avaris into Ramesses (possibly Goshen) puts the arrival of the Israelites at a later date, which is the generally accepted timeline. So, there is no easy way to connect the Hyksos to the Israelites, though something is compelling between their shared experiences.

Shepherd Kings of Egypt

Aside from Josephus’ assertions that the Hyksos were the Israelites, he also quoted Manetho in saying the name given to them had a very different meaning. According to Manetho, citing a sacred and ancient dialect, the syllable Hyc meant king, and Sos meant shepherd. Putting the two together, Manetho believed the term Hyksos meant Shepherd Kings or Captive Shepherds. Modern scholars often dismiss Josephus’ claim that the term meant something other than Ruler of Foreign Lands, attributing it to misinterpretation.

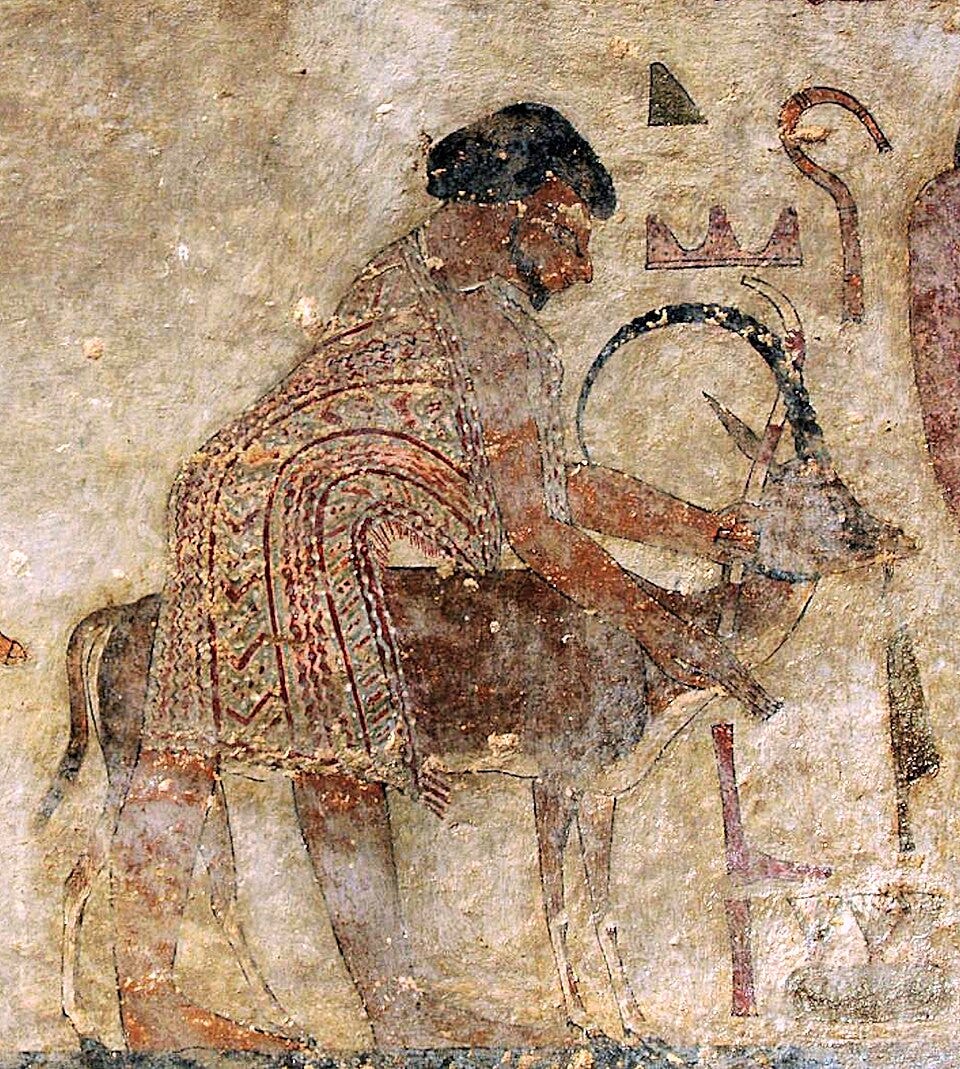

Yet, Josephus argued that the city of Avaris was a country of shepherds, and archaeological evidence may support this. We know, based on architecture and style, that Avaris had a predominantly Semitic population. Archaeology also tells us that Avaris had an abundance of food storage and silos, indicative of a self-sufficient agricultural community. To further support this, Hyksos rulers introduced agricultural techniques to the Egyptians that improved irrigation and crop yield. Let us not forget that these people came from regions of the Fertile Crescent, a region known as the Cradle of Civilization, strengthened by advanced agricultural techniques. Semitic peoples were well-versed in farming and pastoral lifestyles dating back to prehistory. The shears, a tool used to delicately remove wool from sheep, were invented in this very region.

Moreover, there is a rich history of shepherd symbolism amongst ancient Semitic populations. This is well-attested to in Old Testament texts as a representation of divine leadership, of gods and ordinary men. Pliny the Elder remarked on the people of the Near East utilizing sheep for their wool and not their meat. The wool supplied warmth to the human body, and in return, the shepherd cared for and protected the flock from predators. This is why the shepherd makes for an ideal leader; he protects and cares for his flock, essentially being responsible for their continued existence, much like a god to his followers. The divinity is found in its simple yet perfected symbiosis.

These references to the king as shepherd appear to go as far back as ancient Akkadian texts from the time of Uruk and Ur, hundreds of years before the Hyksos and the Israelites. Ancient Sumerian mythology spoke of Tammuz (Dumuzi), god of fertility and agriculture, otherwise known as the shepherd. In Babylonian mythology, the supreme god Marduk was, at times, also associated with the shepherd. In the Enuma Elish, written sometime during the 13th century BCE, Marduk’s creation myth states, “Let him exercise shepherdship over mankind, his creatures.” As the star Nebiru, Marduk is described as “the star that shepherds the gods like sheep.” Hammurabi, a 1st Dynasty king of ancient Babylon, often invoked this shepherd-like quality in Marduk, calling himself the salvation-bearing shepherd.

In ancient Egypt, rulers were not recognized as shepherd kings. However, there are traces of the shepherd if you know where to look. It was said that the reasoning behind Joseph advising his father to inform the pharaoh that he and his people were shepherds was to acquire land separate from the rest of Egypt because the shepherd was, for whatever reason, an abomination to the Egyptians. The irony in this is found in Egyptian symbolism that they evidently may not have even realized or cared to identify with the shepherd.

The timeless crook and the flail that can be seen resting in the hands of the images of pharaohs and the god king Osiris symbolized the king’s protective and giving nature as well as his ability to maintain order and defend his people. The flail, a deadly weapon, can be traced back to the 1st Dynasty. As for the crook, a hooked stick traditionally used for shepherding, it can be traced back to the 2nd Dynasty. Since the founding of a unified Egypt under Menes (Narmer), Egyptian pharaohs attempted to emulate him through pharaonic tradition and imagery. In this way, the shepherd as king is far more subtle, an artistic symbol rooted in a time long passed, one reflecting the lifestyles of prehistoric Egyptians and engrained into society, even as they advanced beyond the perceivably primitive.

It would come as no surprise, then, that the shepherd king imagery would find its way into the Bible. Jesus, David, Moses, Jacob, Abraham, and other prominent figures were said to be shepherds, embodying the shepherd king qualities. Many parallels exist between the transcendent character found in ancient biblical scripture and the lifestyles and mentality of ancient Semitic populations. The shepherd king was the epitome of strength, resilience, compassion, and justice. Stories, traditions, and myths carry over, despite their seemingly simplistic origin. As we have seen, it is not at all uncommon to see the remanence of prehistory, visualizing symbiotic mechanisms in the natural world and amongst groups of people and applying it to the divine, as part of the evolution of religious beliefs and ideologies.

A Shared Heritage

Without a doubt, there are a multitude of coincidental correlations between the Hyksos, the biblical Israelites, and the symbolism of the shepherd king. Though there is no consensus, it is blatantly obvious that these groups of people came from Semitic regions and were given or gave themselves identifiers at a later time. It is quite possible that the Israelites, or Hebrews as they would have been called, were at least in some part linked to the groups that migrated around the time of Avaris and may have remained after the Hyksos’ downfall.

Historically, people of Semitic regions were known to be nomadic. Therefore, there is a strong likelihood that all of those who arrived in Egypt, despite their later names, were from various locations, migrating at varying times in nomadic bands and found camaraderie among people of a shared heritage. It is equally likely, based on this heritage, that the Hyksos would have thought of themselves as shepherd kings. Egyptologists and scholars in the field may dismiss it, but that may be due to a lack of definitive evidence. From a sociological standpoint, migrating groups introduced into a new region tend to form distinctive cultures of their own, blending their heritage with their new environment.

We must also remember: ancient history was not written in the way it is today. Most ancient historians were essentially compilers, gathering information and accounts, not necessarily to prove anything, though there are a few exceptions. Perhaps the answers to the many unknowns surrounding the Hyksos and their relationship to the Bible are not found in theories and speculation, but in the commonalities of all their people in Egypt and the nature of belonging.

Featured Image: Hyksos sphinx. Created during the reign of Amenemhat III (12th Dynasty), later reworked and reinscribed by Hyksos rulers, including Apepi. Cairo, Egypt. (art of line / Shutterstock)

References

Mark, J. 2016. Second Intermediate Period of Egypt. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Second_Intermediate_Period_of_Egypt/

Eames, C. 2023. The Hyksos: Evidence of Jacob’s Family in Ancient Egypt? Armstrong Institute of Biblical Archaeology. Available at: https://armstronginstitute.org/835-the-hyksos-evidence-of-jacobs-family-in-ancient-egypt

Josephus, F. Translation by Whiston, W. 2008. Against Apion. The Project Gutenberg. Available at: https://www.gutenberg.org/files/2849/2849-h/2849-h.htm

Heidel, A. The Enuma Elish: The Babylonian Genesis: The Story of Creation. The University of Chicago Press. Available at: https://archive.org/details/the-enuma-elish-the-babylon-genesis-the-story-of-creation.-by-alexander-heidel

Ivy, J. 2010. Shepherd as King in the Ancient Near East. Academia. Available at: https://www.academia.edu/2603645/Shepherd_as_King_in_the_Ancient_Near_East

The Biblical Timeline. Joseph. Available at: https://www.thebiblicaltimeline.org/joseph/

Excellent & well reasoned - and I agree with your statements. Even if "Hebrew" and broader group "Hyksos", spanning a loose stream of arrival over time, were not "one & same", they were certainly both "Levantine". Conventional historians converge and form a stoic common opinion sometimes with one base error assumption. **Maybe not all readers are aware of the Egyptian Pharoah "standard declaration" regarding 1. Rebuilding sites damaged (by some kind of foreign force) 2. Extending sacred sites better than any predecessor, and from Hatshepsut onwards, 3. Divine birth 4. Driving out Hyksos and rebuilding their desecration, when it is established that that the expulsion of these Eastern Delta dwellers had been completed before Hatsheput's reign: too much too often is incorrect by assigning a literal meaning to standard statements of Pharaohic legitimacy. **Overall, this site produces really excellent material - congratulations!

Read ‘worship of the dead’ by John Garnier…

the Hyksos were Shem & his people… Shem beheaded Nimrod (Osiris) due to his wickedness, and after staying in Egypt for a time, later moved to Salem.