The Making of Legends: Who Were the Minoans?

Featured Article

By Jess Nadeau

On a rugged island shaped by the sea, the earliest hints of a remarkable people appear as stone tombs around 3000 BCE. Roughly a thousand years later, elaborate palaces, a sophisticated hieroglyphic system, and a taste for vibrant art marked their transition into a distinct and thriving society. Settlements sprawled around central complexes, vast palaces with grand courts, theatres, colonnades, lively frescoes, crypts, and drainage systems. Lightwells illuminated a labyrinthine design that reached over four stories high and thousands of square meters. Even as earthquakes and fires ravaged, palaces were rebuilt with renewed vigor. Still, these were not people determined to use their power to conquer; rather, they remained relatively peaceful. Their culture, traditions, and air of mystery effortlessly captivated lands, inspired legends, and forever left the world wondering who the Minoans of Crete truly were.

A Colorful Culture

There were four principal palace sites on Minoan Crete extending over three or four time periods, depending on the source. Sir Arthur Evans, an early 20th-century archaeologist who had given the Minoans their name after the legendary King Minos, divided the civilization into three periods based on pottery styles: Early Bronze Age (3000-2100 BCE), Middle Bronze Age (2100-1600 BCE), and Late Bronze Age (1600-1100 BCE). Greek archaeologist Nikoloas Platon divided time periods into four palatial periods based on historical events. Either chronology works, though both have since been challenged. Palace sites such as Knossos, Phaistos, Malia, and Zakros rose up independently around Crete’s hillsides and mountains, each serving as administrative, trade, religious, and surplus centers.

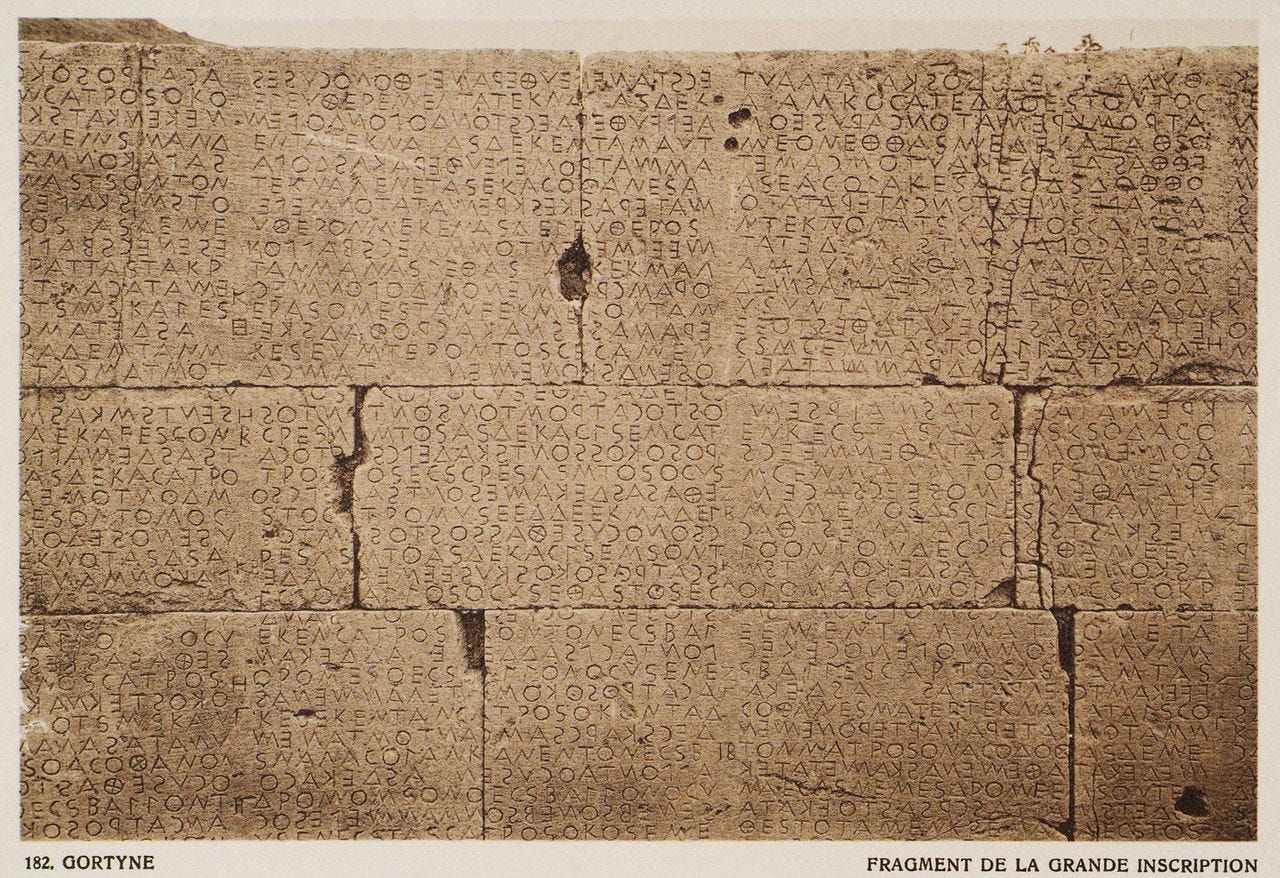

Around 1700 BCE, the growing authority of Knossos, coupled with the emergence of Linear A, a new writing system that replaced the earlier Minoan hieroglyphic script, both of which remain undeciphered, served to consolidate political control across the region. Nevertheless, these communities had always managed cordiality; there was little need for fortifications, aside from the occasional guardhouse or watchtower along roads leading to each palace, keeping bandits at bay. That does not mean, however, that they were unprepared. The double axe, the labrys, and the mighty bull were steadfast symbols of their society. They crafted swords, daggers, armor, helmets, and practiced archery and defense tactics. As a seafaring society, the Minoans traded widely across the Aegean and beyond, reaching the Near East and Egypt. Motifs found at Avaris, the Hyksos capital, attest to their influence, as does their later colonization of the Cyclades during the Middle Bronze Age.

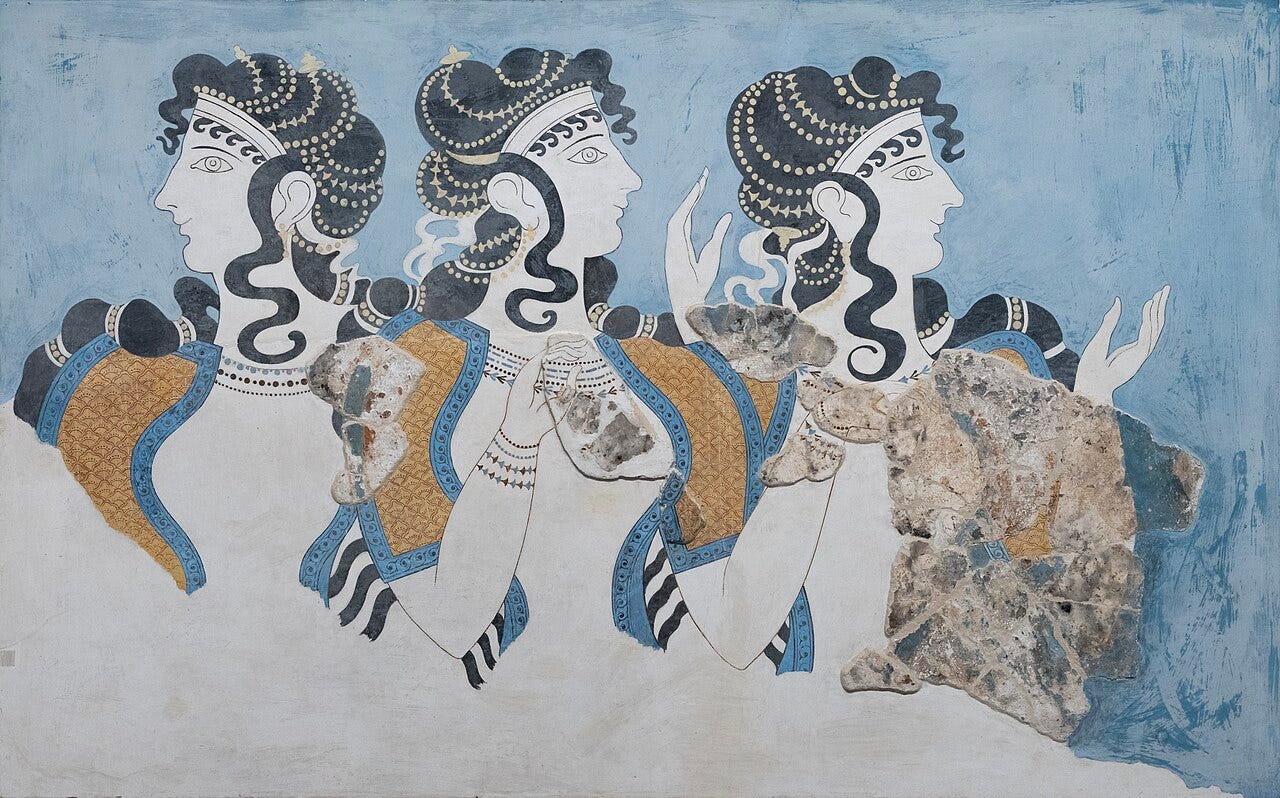

Vessels, ranging from large storage containers to small cups, amphorae, beakers, and the like, were characterized by their intricate early geometric designs, later incorporating striking naturalistic scenes of flora and fauna. The Minoans were the first to depict animals in their natural habitats, absent humans. Dolphins frolicked beneath waves, or an octopus wrapped its tentacles around a vessel in an ever-present state of movement. Frescoes found their way into every corner of a room, stretching across ceilings and onto floors, framed by geometric borders and vivid scenes of the same flowing movement. Men were depicted with their skin red, wearing loincloths, while women wore long, multi-layered skirts and open-fronted bodices, revealing their stark white skin against their embellished jet-black curls. Painted figures leapt, picked flowers, carried vessels or a bundle of fish. Monkeys, birds, and sea creatures cascaded across walls. Small figurines fashioned from bronze and other materials showed deities with arms outstretched or bulls suspended in the air.

The Sacred Bull

The lively images that adorned Minoan architecture and material culture also told a story about who they were, their religion, and practices. Indeed, there is not much known about the religion of the Minoans, due to what remains and an undecipherable script. Myths and legends of later years aside, what can be said is that they were a people who honored Mother Earth in the form of a goddess, one who held serpents in her hands or coiled round her arms. Other figures of deities show much the same, a reverence towards animals and nature. Images, wells, and channels found within palaces indicate offerings of libation. Vast courtyards expectedly catered to grand celebrations and sporting events. Processions, feasts, and ceremonies can be seen in stunning detail. The many caves and hilltops that scatter Crete’s exquisite landscape also show evidence of cultic ritual.

Outwardly, the bull was everywhere. It is found on shrines, ceremonial axes, palace art, cultic imagery, sealstones, vessels, and figures. The rhyta, a vessel specially crafted for the elite, replicated the head of the bull. Additionally, the bull has been seen in sacrificial and funerary contexts, its head housed in its own room within a tomb or its horns decorated with flowers or the labrys upon painted coffins, larnakes. In other, more prominent displays, these horns, made of stone or clay, often flanked the roofs of Neopalatial or Middle to Late Bronze Age structures, including temples and shrines. Sir Arthur Evans referred to these extravagant displays as horns of consecration. As a visible symbol of sacrality, the horns likely embodied the bull’s immense strength and fertility, comparable to other neighboring cultures.

The Greeks believed the horns to be a powerful symbol, linked to the Greek god Zeus, his wife Hera, as well as Dionysus and Heracles. Also common was the sacrifice of bulls in honor of the Olympic Games, with a purported 100 bulls being killed at its commencement. Thighs and bones burned, carrying billowing smoke to Zeus, while the people fed on the rest. In ancient Egypt, bulls represented a similar power, linked to kingship, Hathor, Amun, Ptah, Isis, and Nut. The solar disk sat between its horns as a crown of divinity. The Apis bulls, worshipped in Memphis as a manifestation of Ptah, enjoyed royal treatments and elaborate burials. In the Old Testament, horns of the altar, projections on each corner of a bronze altar, were used to bind an animal, destined for sacrifice; its blood was then smeared on the horns.

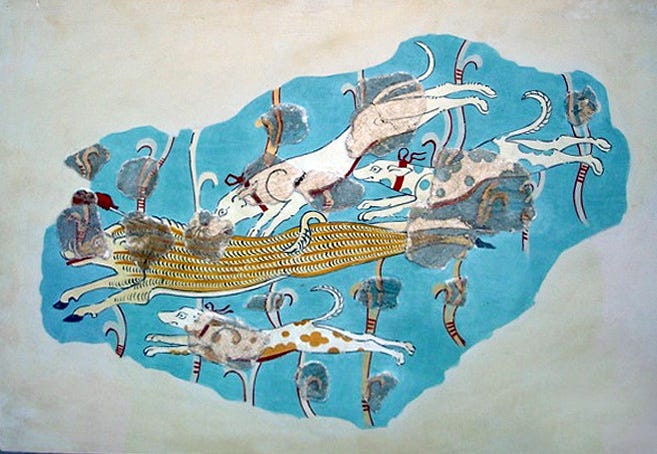

Clearly, the bull had an impactful impression on ancient civilizations throughout the Mediterranean. Still, the Minoans took sacred bull worship to another, more eventful level. Beginning sometime during the early Late Bronze Age, artistic representations found in Knossos show the acrobatic sport of bull-leaping. Broken down into four phases, participants would cautiously approach a waiting bull, grasp at its menacing horns, and launch over its back, landing firmly on the ground. In some cases, women can be shown holding the bull’s horns as men flung over, while additional women wait to catch tumbling bodies as they land. Grand courts were the presumed location of these exhilarating games, and it was common, based on frescoes, that ladies of status were in attendance; their images large and pronounced. Even Plutarch had commented on the customary practices of women viewing the games in The Life of Theseus.

Some scholars have dismissed the bull games as symbolic representations of religious rites, claiming it is nearly impossible; yet, this is far from the truth. While select images show the bull in varying positions, which may be accommodating, acrobatic acts involving bulls are nothing new to modern sport. The Course Landaise, a non-lethal form of bullfighting found in southwestern France, involves similar feats of athleticism to evade charging bulls. Given the bull’s religious significance, the games on Crete may have been trained or untrained demonstrations of strength and vitality, victories won over nature, rites of passage, or homage to the gods.

Interestingly, the bull games may have also included other forms of sports, particularly wrestling and boxing. Combatants may be shown wearing gloves, guards for the forearms, and at times, helmets and weapons. Depictions differ in equipment styles for participants, suggesting that some may have sported heavier wear while others remained scantily clad. Certainties of complementary athletic games are still hazy; however, this combination of events did inevitably find its way into Mycenaean funerary traditions, which may provide further support. Evidence found on a Mycenaean sarcophagus suggests that the culture adopted the bull-leaping sport as well as armed combat as a part of funerary games.

Women in Minoan Society

As mentioned earlier, frescoes depicting the famous bull games show women not only as prestigious spectators, but also as participants. The portrayal of women in this sort of hierarchical scale compared to their male counterparts may signify their status among spectators, shedding light on women’s position in society as noticeably active, contrary to the Greeks, apart from Sparta. Classical writers, such as Plato, Thucydides, Strabo, and Plutarch, had touched on women in Minoan society having certain freedoms in daily activities and sports, and administrative records written in Linear B provide a plethora of information on the status and work of Mycenaean and Minoan women. On tablets found in Pylos and Knossos, women are methodically classified based on socioeconomic status, expressing a clear hierarchy. Women were also equally integral to the labor force, free to work in skilled and unskilled trades.

Though evidence is lacking as to whether or not women held sovereignty, it is known that they were deeply involved in religious practices; priestesses—as well as priests—had ample sway, spiritually and politically. Their graves, specifically those of priestesses, were found to contain a wealth of lavish goods. Later inscriptions, like the Gortyn Law Code, written in Dorian Greek between 700-600 BCE, are believed to outline laws that once existed in Minoan society. Among the laws, ranging from slave ownership, adultery, divorce, inheritance, property, and so on, there is a degree of favoring towards women. As an example, in the case of divorce, a woman was granted property rights, including anything that she had contributed to the marriage, half of any joint income acquired from property, and a generous portion of household items.

Evidence would indicate that women had far more administrative authority than what later generations would generally allow. Some have argued, based on this evidence, that the Minoans were a matriarchal society. That the presence of a female supreme deity, cultic iconography that revolves around priestess activities, hierarchy of scale in artwork, and administrative agency points to a female-dominated culture, one that may have been historically diminished by patriarchal ideologies. Many of these arguments are, unfortunately, based on modern thought. Given that a proper king’s list does not exist, and the majority of written records are from later dates, it is difficult to determine exactly how men and women interacted politically. If the Minoans operated under a patriarchy, which is likely, the contributions of women in economic, sacerdotal, and athletic roles are undeniable and emblematic of a people immortalized for their refined sophistication.

Theseus and the Minotaur

Disguised as a bull, Zeus carried Princess Europa across the sea to Crete, where she bore a child, naming him Minos. The man would later become the king of Knossos, celebrated for his naval mastery and prosperity. Though Minos did well for his country, he held a dark secret. To legitimize his rule, he once prayed to the god of the sea, Poseidon, asking him for his favor. The god answered with a brilliant white bull that emerged from the sea, a gift intended for sacrifice. So enamored Minos found himself with the handsome bull that he chose to sacrifice one of his own in its place.

Thus, Poseidon cast a spell on Pasiphae, Minos’s since faithful wife, to fall madly in love with his bull. Pasiphae, now possessed by a primal obsession, went to Daedalus, master craftsman and architect, to craft her a cow that she could enter and mate with the bull. Her desires soon manifested into a child, one born with the body of a man and the head of a bull, the Minotaur. Appalled, Minos then ordered Daedalus to build a network of tunnels beneath his palace, a labyrinth to house the horrific beast. Every nine years thereafter, Athens was forced to surrender seven young men and seven young women to Crete to satiate the Minotaur.

Infiltrating another pledge of victims, the hero Theseus was determined to end this brutal tradition. Purposefully, he wandered through Minos’s palace of endless corridors, passageways, and shadows until his gaze was unexpectedly met by Ariadne’s, Minos’s beautiful daughter. Instantly enchanted, Ariadne heard his tale and offered aid, giving him a ball of thread to mark his path through the labyrinth. Navigating the dreadful tunnels tested his strength and endurance, but would ultimately lead him to his ominous foe. Theseus succeeded in slaying the beast, followed the thread to his escape, and fled with Ariadne.

Minos’s fury turned to Daedalus and his son Icarus, whom he swiftly imprisoned in the very labyrinth that Daedalus constructed. Fashioning wings from feathers and wax, father and son chose to escape by air. But in Icarus’s haste, he flew too close to the sun. For a brief moment, he triumphed in the sun’s glory, only to feel the burn of melting wax upon his skin and watch the feathers of his wings flutter away. He fell to his death, washed away by the sea. Daedalus would survive, taking refuge in Sicily.

These tales were how the Greeks remembered the Minoans. Earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, tsunamis, and the rise of their mainland neighbors, the Mycenaeans, left their land conquered and their palaces abandoned. By 1200 BCE, most Minoan sites were in ruin, while piratical groups began claiming their coastlines. It wasn’t until the 8th century BCE that archaic Greeks colonized Crete. Not all was lost, and as such, there are several ways to connect myth and legend to what is known about Minoan civilization, their architecture, traditions, and symbols.

Theseus’s heroic adventure into Crete is centered around the bull, the Minotaur, and he, as well as the other sacrificial victims, are youths. Considering that the bull games may have been a rite of passage or perhaps a trial of strength, it parallels Theseus’s experience in overcoming the bull and his introduction into a love relationship. Though Ariadne and Theseus never wed, their series of events mimics coming-of-age or rites of passage, which prepare youths for adulthood and eventually marriage. The labyrinth is noticeably defined in the complexity of Minoan palaces as well as the symbolic labrys. Etymologically, it is believed that the Greek word labyrinthos (labyrinth) is derived from labrys (double axe) and inthos (place of), roughly meaning place of the double axe, or more appropriately, House of the Double Axe.

There is, however, another explanation that accounts for the labyrinth structure being underground. In Cretan versions of the legend, the youths were never victims of sacrifice, at least to the bull, but rather prizes meant for participation or sacrifice in Androgeus’s funerary games, much like later Mycenaeans incorporated bull games and combat sports into funerary tradition. In this case, the subject is the son of King Minos—the Minotaur was the product of an affair, but similarly linked to Minos. Victims may have been held temporarily in an underground holding area within the palace complex, being trained or untrained in the sports that followed. The bull games were most certainly dangerous; death or severe injury was inevitable. The contests themselves, much like gladiatorial games, were evocative to the spectator, terrifying to the participant, but also a symbol of bravery.

Subtleties in written accounts, like those of Plutarch and Philo of Alexandria, point to a highly plausible scenario in which the legend may be purely fantastical based on actual events. That Theseus did not necessarily travel to Crete to stop the Minotaur, but to participate in the bull games and accompanying sports. Iconography, as well as these written accounts, suggests that the games may have been exclusive to Minoan elites. Taursus, another name for the Minotaur, may actually be a general of Minos’s army to whom Theseus was granted permission as a foreigner to wrestle. It is still possible that Theseus wrestled a bull, as gems found in Crete, dating to the Minoan era, show men actively wrestling with bulls, rather than leaping over them. Additionally, the legendary Heracles famously wrestled and subdued the Cretan Bull during his seventh trial.

Inspiration and Modern Myth

Whether bull sports were funerary, celebratory, rites of passage, or a combination of sorts, they were entrenched in Minoan culture, recognizably diverse, and utterly fascinating to outsiders. Those most notably influenced by the Minoans were the mainland Mycenaeans, who, according to popular consensus, invaded Crete and its surrounding islands sometime around 1450 BCE. At this time, and the decades leading up, the Minoans had been fortifying and storing, indicative of war preparations. It is also during this time that Crete began using Linear B, an adaptation of Linear A widely used by the Mycenaeans.

The best evidence is found through artistic motifs of bulls and sea life, pottery, frescoes, and metalworks. Though most Mycenaean artwork has a military focus, clear inspiration can be drawn. Palaces at Mycenae, Tiryns, and Pylos were similar in design to the elaborate palaces of Crete, despite having their own architectural traditions. Grave goods originate from Crete, the double axe, a religious pantheon with a principal female deity, and religious symbolism, all carried on fluently.

The origins of perhaps the greatest oracular site in ancient history, Delphi, transpired as Apollo defeated an enormous she-dragon, the serpent Python, to establish a site for his oracles, then transformed into a dolphin to bring priests from Crete to run his temple. The specificity of a female snake deity and Cretan priests echo beliefs, traditions, and practices that originated in Crete. If the Minoans had something similar to a theocratic system of governance, whereby rulers were associated with the divine and religious leaders were revered and sought after, it is no coincidence that Delphi was at the center of political counsel, bending the will of the powerful. Their oracles, the Pythia, also enjoyed a level of prestige compared to other sites.

In modern times, the Minoans are often associated with the otherworldly lost city of Atlantis. Plato’s description in his dialogues Timaeus and Critias (360 BCE), handed down from an Egyptian priest to an Athenian statesman, tells of a mysterious city with wonders and advancements beyond their time. Their city was curiously designed, trade networks were extensive, granting them exceptional wealth and a superior navy. A natural disaster struck within a day and night, leaving Atlantis to fall into a watery abyss.

The connections are compelling. Natural disasters destroyed Thera around 1600 BCE, a Minoan colony. It is no secret that the region had repeatedly dealt with natural disasters, as was the case with the rebuilding of all Minoan palaces on Crete during the Late Bronze Age. Trade was known to occur in distant regions, including Egypt, which supports the Egyptian record of such a place. Plato had also mentioned bull sacrifice, and Thucydides claimed that Minos built the world’s first navy. However, inconsistencies outweigh evidence. The time period, location, and the oddly specific nature of Atlantis do not match current archaeological data.

For now, at least, Atlantis is a myth or may be located in some other far-off place that is beyond the scope of this article. In any case, the Minoans left a mark on not just the ancients but modern society as well. Their rare exceptionality speaks to a world where conflict is not invited, where tradition, myth, and legend collide. In the ancient portrayal of Minoan society, and what is known about them now, albeit not complete, they may certainly be the epitome of mythifications of history. Mythology has never been simple storytelling to explain the world or to give life to deities; it is also based on histories, oral and written. What the Minoans give, truly, is a definitive glimpse into how and why mythification occurs. In a place that defied convention, so extraordinary and well preserved in its expression, its influence could not help but drift across lands and imaginations, becoming lasting myth and legend, like a fair wind carrying a ship across the sea.

Featured image: Ladies in Blue, Knossos (Heraklion Archaeological Museum, CC0)

References

Cartwright, M. 2018. Minoan Civilization. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Minoan_Civilization/

Macquire, K. 2020. The Minoans & Mycenaeans: Comparison of Two Bronze Age Civilisations. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/article/1610/the-minoans--mycenaeans-comparison-of-two-bronze-a/

Scanlon, T.F. 2014. Women, Bull Sports, Cults, and Initiation in Minoan Crete. Sports in the Greek and Roman World. Oxford University Press. Available at: https://www.google.com/books/edition/Sport_in_the_Greek_and_Roman_Worlds/mGcJBAAAQBAJ?hl=en&gbpv=1&dq=female+athletes+minoan+society&pg=PA28&printsec=frontcover

Mclnerney, J. 2011. Bulls and Bull-Leaping in the Minoan World. Expedition Magazine. Available at: https://www.penn.museum/sites/expedition/bulls-and-bull-leaping-in-the-minoan-world/

Pedley, J.G. 2012. Greek Art and Archaeology – 5th Edition. Pearson Education, Inc.

Plutarch. The Parallel Lives – The Life of Theseus. Loeb Classical Library, 1914. Available at: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Theseus*.html

Plato, translated by Waterfield, R. 2008. Timaeus and Critias. Oxford World Classics, Oxford University Press.

Fantastic Writing. Thank you!

Truly inspirational, thank you.