Warriors of the Sea: Tracing the Origins of Pirate Culture

Featured Article

By Jess Nadeau

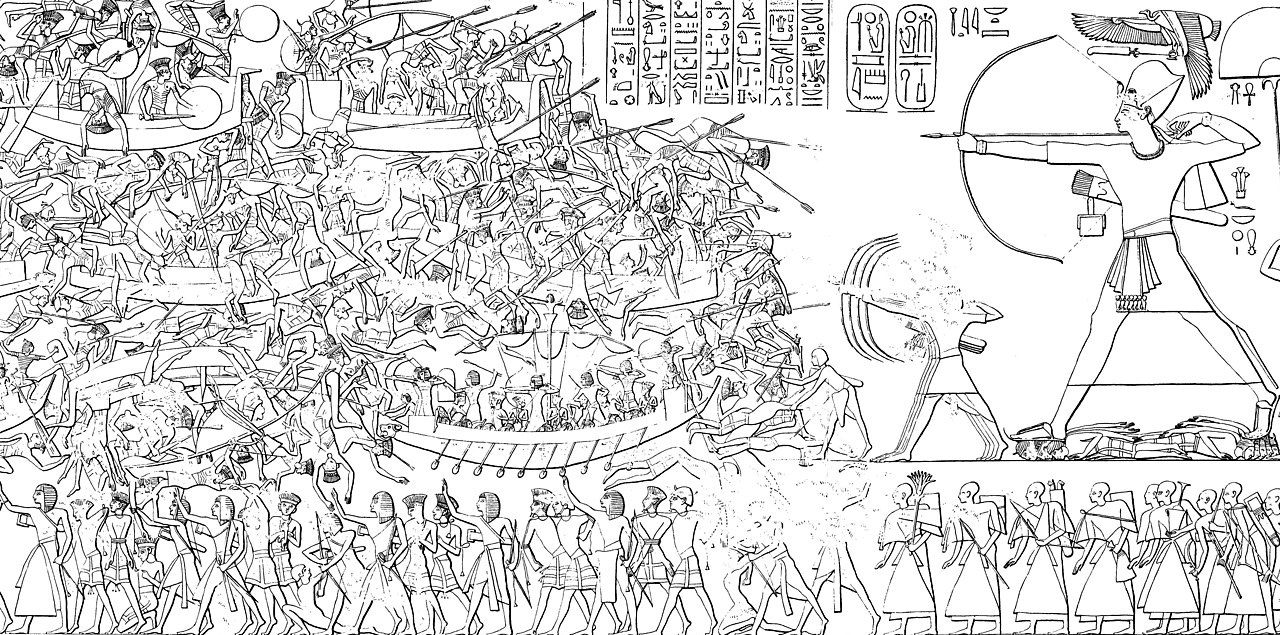

Kingdoms across the ancient world were gripped by confusion during the 14th century BCE. Egyptian and Near Eastern coastal cities were being ransacked by marauders, while rulers hurled accusations at one another in desperate attempts to uncover the culprits. Their surviving correspondences echo mutual frustrations, an omnipresent sense of uncertainty that hung over the Mediterranean world. Akhenaten wrote to the king of Alasiya, accusing him of the treachery facing his kingdom, only to be reminded that their plight was shared. Some had an inkling as to who these mysterious marauders were. The Hittites spoke about the Lukka, a group with indeterminate territories in Anatolia, or perhaps it was the Sherden, the very same seafaring mercenaries the Egyptians employed throughout their military.

No matter, something was clearly churning in the waters that sustained these ancient societies. Two centuries later, the mechanisms of societal collapse that defined the end of the Bronze Age were devastating for some but liberating for others. Those who worked tirelessly for meager rations, laboring away in cramped, unsanitary, and dangerous conditions, were given an opportunity. Ship builders, rowers, textile and construction workers often faced harsh conditions and even harsher punishments. Uprisings of the working class through the end of the Bronze Age and into the early Iron Age only fueled an already raging fire. With natural and economic factors merging into a frenzy, social structures crumbled, wars broke out, and unexpected alliances formed. Catastrophe inevitably forged new identities, products of desperation and adaptation, guided by the merciless sea, and thus, the pirate was born.

Emerging Tribal Identities

Before the rise of the infamous Sea Peoples, piracy had already begun to establish itself in the Mediterranean. As trade expanded, so too did opportunities for acquiring wealth. But for the many, wealth was reserved for the elitists of their society, and they were forced to endure at the will of those in power. When societies began to fall, any means to a sustainable living were forfeit; starvation, disaster, and droughts withered away the resilient. Through this unfathomable series of events, those who were once a nuisance found camaraderie at the sea. The Sea Peoples, so well-known for their plundering and devastation, laying waste to cities, came from no single place. They were a collective, one that did not live by the laws of the land and saw no reason to submit to the leaders who failed them.

“Not one stood before their hands… They desolated his people and his land like that which is not… they lay their hands upon the land as far as the Circle of the Earth. Their hearts were confident, full of their plans.”

Ramesses III temple inscription, Medinet Habu. Breasted translation, 2001

When Ramesses III defeated the Sea Peoples in 1178 BCE, sparing his kingdom from their wrath, they disappeared from historical records. Others were not so lucky. New kingdoms emerged in the wake of destruction, rebuilding their societies from the ground up. But the Sea Peoples were not gone; some had assimilated back into society, leaving their undeniable mark on cultures, while others embraced the piratical lifestyle and would later become the pirates of future generations. What can be said about the Sea Peoples is that they built a fully self-governing and self-supporting society of their own, flourishing in the shadows of expansion and interdependency. They came from various geographical locations, religions, and cultures, working together through common aspirations. What defined them, and continued to define piratical activity thereafter, was their tribal nature.

Historically, tribalism is a form of egalitarianism, based on a system that embraces equal distribution of work and wealth. As such, it may be more informal than that of other social organizations like chiefdoms or city-states, whereby an individual or close-knit group, usually granted through hereditary rights, holds sovereignty. Therefore, the basis of pirate culture relied on the equality of its people, which was in stark contrast to the types of societies prevalent at the time. This is why piracy served as an opportunity for those less fortunate; it enabled a form of equality that may not have been afforded to them in their past lives. Their newfound identities revolved around social behaviors that entitled each of them to rewards—food, plunder, and drink—that they did not have to surrender to a higher power. In this freedom, patterns of behavior evolved into a social order of its own.

Undoubtedly, leaders were chosen, but the choice may have been based on merit rather than hereditary affiliations. Likely taking Indo-European titles, pirate leaders would have called themselves tawaris, the warlord, among other commendable titles. Several tribes could have been under the same leadership, sailing the seas under their own tribal names. In time, as tribes exponentially grew through the seizing of new ships and resources, they would split off and form new tribal groups with new leaders. For piracy to be at its most effective, groups needed to remain small, agile, and efficient. In essence, this configuration is reminiscent of hunter-gather societies, moving from place to place in similarly small groups, gathering resources, and then moving on. Contrary to common belief, pirates, even in those early days, did not plunder anything and everything. Their choices were meticulous to ensure that survival at sea was sustainable.

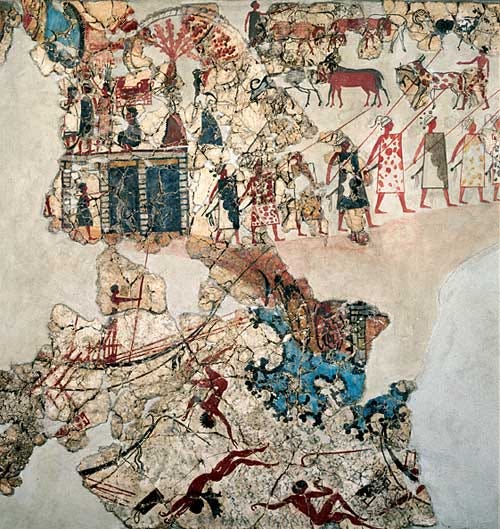

Symbols of Unification

Because the Sea Peoples came from multi-ethnic backgrounds, it propagated cultural exchange. Through archaeological records, early pirates shared their native material cultures and traditions in inventive maritime ways, having strong ties to Aegean and Italic cultures, as well as others throughout Anatolia. Their ships, small and easily navigable, were their homes, their kingdoms, and a symbol of their identities. At the prow of their ship sat the head of a bird. On their bodies, the regalia of a true warrior of the sea. Horned and feathered helmets likely adorned their heads, stylized to their liking, and unifying them as a tribe or collective. These helmets also linked them to people, like the Sherden or Anatolians, who were known, along with some of their deities, to wear the horned or feathered helmet. Emblems, spiraled patterns, pottery, weaponry, and wares shared common features inspired by their multi-ethnic heritage, yet transformed into something new.

The feasts in which pirates shared after a successful pillaging campaign mirrored the once grand celebrations that were only offered to them through the palaces of their leaders as a steadfast reminder of the social hierarchy that existed on land. Without the palace to grant them extravagant feasts, they were free to celebrate at their leisure. Gathered around immense hearths that scattered their coastal retreats, they feasted and drank, reminiscing on spoils and conquests. Drinking in excess became an act of unification between a single crew or separate tribes, a symbol of their communal spirits. With all that they had acquired, all they were set to gain, there was nothing to hoard. In these simple acts, they were equals.

Expectedly, there was more required of the pirate lifestyle than feasting, drinking, and pillaging. The organization of any given ship needed a skilled crew. Some were ranked based on skill: fighters, rowers, builders, doctors, and others. Still, even the unskilled were given jobs, though their share of spoils may have been slightly affected. Nonetheless, everyone aboard functioned and benefited from the arrangement. Working together, their tactics proved efficacious. Practical ships easily beached on moonlit shores, allowing them to slip into cities without much of a fight. Successes depended on the element of surprise. Structures were destroyed, agricultural fields burned, and people fled in panic, as they ravaged what was theirs for the taking. If the land was suitable, they could then effortlessly claim it as their own, feasting beneath the flames of ruin.

Though many cities were left as abandoned rubble, the land that became pirate rendezvous, hideouts, and lookouts was strategically chosen. The Mediterranean was plentiful in rocky outcrops, sheltered creeks, coves, straits, capes, and promontories. Turbulent seas meant that trade ships skirted the coastline, leaving them open to attack. Pirates hidden by rocky cliffs or watching ominously from promontories that hung high above the waters could easily overtake a vulnerable ship. Capes and straits provided the perfect choke points with little time for merchants to evade. They founded their havens in advantageous locations, where ships could be spotted and the element of surprise was their loyal ally. In places desolated by pirate attacks, such as Crete, those who remained migrated further inland, leaving the coast abandoned to piratical occupation. Attempts to subdue only strengthened their resolve. Numbers grew faster than any one society could withstand. Myriads of Aegean islands became the triumphs of rogues.

The explosion of piracy brought on by the Sea Peoples inevitably fed on the failures of strained institutions. However, despite pushback long after the world recovered, relics of a past cultivated in chaos metamorphosed into a functioning enterprise, welcomed and adopted by the very people who once sought to end them. Not only did pirates receive willing members, many of whom came from shattered cities, but they also took by force. The slave trade was nothing new to Iron Age people. Clever tricks and well-organized assaults were leverageable skills. If slaves were not sold, reconciliation lived aboard the ship of their captors. Their rites of passage were dependent on proving themselves worthy and reveling in their rituals. For the societies that relied on slave labor, pirates were formidable collaborators.

Blurring the Lines Between the Political and the Piratical

As the slave trade became more lucrative, so too did those who participated in it. Pirates were employed, kidnapping and selling citizens at slave ports with full profits. Legitimate traders were also quick to transport slaves who sold themselves or their children, or even engaged in kidnapping, all the same. Demand for slaves far outweighed moral reason, and the ease of acquiring human cargo with little expense made for a rewarding living. Power and influence in the Greek Mediterranean, along with approved slave acquisition by any means, meant that piracy at this time was a tool rather than a hindrance. Further indifference to piratical activity led to the Greek implementation of the marauder strategy for wartime efforts, targeting political adversaries, capturing fleets, and sailing away with riches. Indeed, crews needed approval by the state, and spoils needed verification as belonging to the enemy, with some expectedly turned over to the sponsored city-state.

The lure of perceived fortuitous transgression enabled anyone to fit a small ship and assemble a crew of fellow peasants. Any fisherman or builder would have been well-acquainted with the necessary skills in maintaining a lifestyle at sea aboard small limbus crafts, and the opportunity for upward mobility likely mollified hesitation. So common and ingrained in everyday affairs, even the great writers of the time celebrated or told tales of the pirate’s life. Homer gave some of the earliest written descriptions of piratical motivations: thrilling exploits, sacking cities, women ready for the taking, feasts of lamb, and copious wine. Thucydides considered them somewhat primitive, yet honorable in their pursuits.

“For in early times the Hellenes and the barbarians of the coast and islands, as communication by sea became more common, were tempted to turn pirates, under the conduct of their most powerful men; the motives being to serve their own cupidity and to support the needy. They would fall upon a town unprotected by walls, and consisting of a mere collection of villages, and would plunder it; indeed, this came to be the main source of their livelihood, no disgrace being yet attached to such an achievement, but even some glory.”

Thucydides, 1.5

Herodotus raved about Polycrates of Samos, a 6th-century BCE pirate warlord with 100 ships at his command, frighteningly competent in his naval mastery. Though not so competent when he fell for a trap that led to his crucifixion. A 7th-century Homeric Hymn told the tale of the abduction of a beautiful boy in favor of Dionysus, the god of madness, by the Tyrrhenians. Vines sprang from the wooden boards of their ship, beasts flowed like water through their cracks, and the men transformed into dolphins. The Etruscans, also referred to as Tyrrhenians—an ambiguous term the Greeks often used for pirates or ethnic groups in Italy—were synonymous with piratical aggressions. Perhaps a product of negative propaganda, most Etruscans were merely armed traders. Regardless, the blurring of lines between pirate and policy made identification of aggressors a challenging obstacle. For those who ventured out to sea, anyone could be a pirate. Such a predicament did the Greeks find themselves in that attempts at limiting unchecked piratical reign were short-lived. Alexander the Great’s international coalition against piracy seemed promising, but it was regularly met with resistance and betrayal. By the time of his death in 323 BCE, his successors resumed a tradition steeped in deception and desolation.

As the Roman Empire trailed the Hellenistic era, piracy had exploded into an unstoppable force. The Greeks had been utilizing pirate tactics for warfare, the slave trade, and petty disputes. Pirates had long taken over the coastal regions of Crete and many of the islands in the Aegean. Powerless coastal cities were either left abandoned, destroyed, or reclaimed by tribes of pirates. A sinister presence threatened any ship that sailed the Mediterranean, probing eyes looming in all directions. Cilician pirates from the south of Tarsus in Anatolia targeted lucrative trade centers. The Illyrians, a highly skilled tribal culture under the rule of Queen Teutra, scourged the seas, provoking Rome with trade disruptions and the killing of an envoy. After two tumultuous wars and the betrayal of her successor, she supposedly leaped from a cliff. But as these things often go, the Illyrians did not keep up their end of the deal with Rome and hastily returned to their pirate ways until they were finally decimated in 227 BCE.

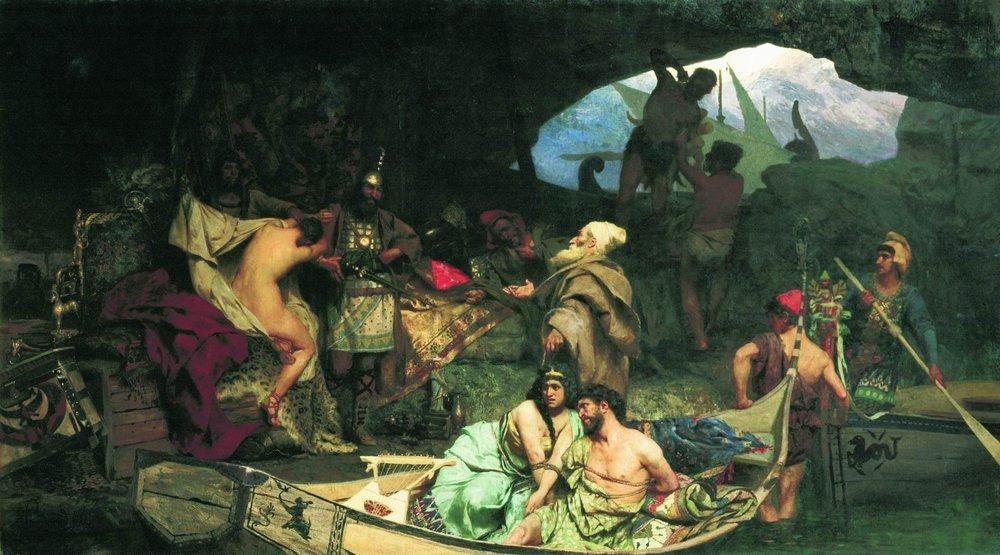

In truth, the Romans had a grave dilemma on their hands. They relied on piracy for slaves, resulting in several extremely wealthy ports, founded on piracy and the slave trade. The faltering of the Seleucid Empire only bolstered the Cilician pirates, and even as Rome moved to annex the region in 190 BCE, nothing could deter their growing numbers. Emboldened by unbridled ambitions, dignitaries were killed, war efforts thwarted, merchants ruthlessly attacked, and travelers tricked into trade were kidnapped and sold as slaves. Rhodes endured relentless assaults, their navy on the verge of collapse. Fortifying ships and patrol routes proved successful, but only for a time. In 75 BCE, 25-year-old Julius Caesar was kidnapped by Cilician pirates while in Rhodes. Rather than submit to his captors, he embraced what fate had offered him, going so far as to demand a higher, worthy ransom for his return.

“For eight and thirty days, as if the men were not his watchers, but his royal body-guard, he shared in their sports and exercises with great unconcern. He also wrote poems and sundry speeches which he read aloud to them, and those who did not admire these he would call to their faces illiterate Barbarians, and often laughingly threatened to hang them all. The pirates were delighted at this, and attributed his boldness of speech to a certain simplicity and boyish mirth.”

Plutarch, The Life of Julius Caesar

Means to an End

The abduction of Julius Caesar and the disastrous raids that followed inevitably spelled the end for unbound warriors of the sea. Despite their hefty contributions to the slave trade, the Romans no longer saw sufficient use for them, seeing them as more of a growing encumbrance to the empire. In 71 BCE, Rome waged war on the Cretan pirates. A few years later and through a series of three turbulent conflicts and unprecedented authority, Pompey the Great defeated the Cilician pirates. For the first time, fleets came together, working their way through designated districts assigned to the sea. It was a collaborative effort that paid off. Pirates were driven back, crucified, sold as slaves, or given opportunities for rehabilitation far from the sea’s auspicious repute.

Still, the culture that the Sea People built did not fade into obscurity. The Romans eliminated opposition but continued to utilize the Cilicians in a controlled manner, granting them sanctioned prospects in the slave trade. Through this, the city of Side achieved immense wealth and status, all under the guise of Roman law, and still as deceptive as ever in their tactics. The reality was that piracy never ended; it was simply mitigated as long as it could be contained. Piracy thrived in the Mediterranean until the Middle Ages, not only because it was the birthplace of pirates, but also because it was the perfect geographical location.

Future piratical groups emulated the traditions and tactics of the original warriors of the sea. The notorious Barbary Pirates, spanning from the 16th to the 19th century, were a collective of different ethnicities, all drinking, feasting, and plundering to their hearts’ content, gathering slaves for sale, and expressing their identities through their ships, symbols, and material culture. Among others, the tribal nature of the Vikings, along with their impeccable seafaring skills, made them legendary pirates in their own right. The act of piracy was and has always been based on the unifying nature of the liberation that is found in camaraderie. The tribal affiliation that almost instinctively occurs in piratical formations is the uninhibited release of the chains that bind individuals to the rigidness of hierarchical society. And so, the pirate is not the villain in the world’s story. Though their acts may be seen as deplorable, it is not so different than what feuding nations have inflicted on each other. The rogue’s freewill was never a means to an end, but a means of surviving in a world shaped by brutality.

Featured image: Corsairs (pirate), ca. 1880 by Henryk Siemiradzki (Public domain)

References

Hitchcock, L.A. & Maeir, A.M. 2016. Fifteen Men on a Dead Seren’s Chest: Yo Ho Ho and a Krater of Wine.

Hitchcock, L.A. & Maeir, A.M. 2016. A Pirate’s Life for Me: The Maritime Culture of the Sea Peoples. Palestine Exploration Quarterly, 1-20.

Hitchcock, L.A & Maeir, A.M. 2016. Pirates of the Crete Aegean: migration, mobility, and Post-Palatial realities at the end of the Bronze Age. Proceedings of the 12th International Congress of Cretan Studies, Heraklion.

Mark, J. 2019. Pirates in the Ancient Mediterranean. World History Encyclopedia. Available at: https://www.worldhistory.org/Piracy/

Bileta, V. 2021. Scourge of the Inner Sea: The Pirates of the Ancient Mediterranean. The Collector. Available at: https://www.thecollector.com/ancient-mediterranean-pirates/

Thucydides (translated). History of the Peloponnesian War, Book 1. 1-23. The Latin Library. Available at: https://www.thelatinlibrary.com/historians/thucyd/thucydides1.html

Plutarch (translated). 1919. The Life of Julius Caesar. Loeb Classical Library. Available at: https://penelope.uchicago.edu/Thayer/E/Roman/Texts/Plutarch/Lives/Caesar*.html

I really love the articles by Jess! Thank you for another great one

Aye! Don't ye be disparagin’ the good folks feedin’ the poor orphan fishes!