Against Shadows and Myths: Why Pseudoscience Haunts History, and How We Resist It

Guest Article

There are days when I find myself bone-tired, not of the work of history itself, but of the endless parade of pseudoscientific fantasies that clutter our field. One spends years reading inscriptions, weighing fragments of evidence, learning dead languages, carefully piecing together the lives of emperors, peasants, and poets alike. And yet, when I speak to the public, the first question is not about the fragile empire of Constantine V or the struggles of Julius Nepos. It is: “But what about Atlantis?”

The weariness comes not from disagreement, historians thrive on debate, but from the sheer displacement of history by spectacle. Atlantis, ancient aliens, lost golden ages, biblical literalism, Aryan master-races: the counterfeit past always seems to attract more attention than the real one. This is not a minor nuisance. It is a profound intellectual and social problem, and one that requires both philosophical clarity and historical courage to address.

Why, though, does pseudoscience find such fertile ground in history? And what can we do to resist its seductive pull?

The Lure of False Certainty

The problem is hardly new. Plato, in his Republic, described humanity as prisoners in a cave, watching shadows on the wall, mistaking them for reality. The philosopher’s task was to break free and confront the painful light of truth. But most prefer the shadows. That allegory is a powerful reminder of why pseudo-history persists: it is easier to accept vivid illusions than to grapple with messy truths.

David Hume put it bluntly: “The passion of surprise and wonder, arising from miracles, being an agreeable emotion, gives a sensible tendency towards the belief of those events.” (Enquiry Concerning Human Understanding, X.12). The human mind is not naturally inclined towards scepticism; it delights in marvels. Thus, when confronted with competing accounts, one sober, evidence-based, nuanced; the other spectacular, cosmic, filled with lost continents and hidden secrets, many readers lean toward the latter.

Pseudo-history thrives on narrative clarity. “The pyramids were built by aliens” is a far simpler story than “The pyramids were the result of complex social, economic, and religious structures over centuries, relying on human ingenuity and labour.” False certainty is more comforting than real ambiguity.

Why, though, is history more vulnerable to pseudoscience than, say, chemistry or mathematics? One answer lies in Karl Popper’s criterion of falsifiability. A scientific theory must be open to testing and disproof. History, however, often deals with unique and unrepeatable events. We cannot rerun the fall of Rome or conduct laboratory experiments on the life of Julius Caesar. This inherent difference leaves space for imaginative speculation.

Thomas Kuhn, in The Structure of Scientific Revolutions, showed how science progresses through paradigm shifts, normal science punctuated by revolutions. History, by contrast, does not experience paradigms in the same way. Historians debate interpretations, but rarely do we have the clarity of an Einstein displacing Newton. This makes it harder to decisively dismiss pseudo-historical claims. If one person insists Atlantis existed, how do we ‘falsify’ it beyond the absence of evidence? And as every historian knows, the absence of evidence is not necessarily evidence of absence.

It is precisely this epistemological gap that pseudo-historians exploit. They thrive in the grey zones where absolute proof is impossible, presenting speculation as if it were legitimate debate. The result is a flourishing industry of conjecture, from ‘biblical archaeology’ wielded to prove literal readings of scripture, to nationalist myths that conjure ancient homelands for modern political projects.

Power, Politics, and the Uses of Pseudo-History

Pseudo-history is never innocent. Michel Foucault argued that knowledge and power are inseparable: ‘We should admit… that power produces knowledge… that power and knowledge directly imply one another.’ (Discipline and Punish). To control the past is to control identity, legitimacy, and authority in the present.

This is why pseudo-history has been so potent in politics. The Nazi myth of Aryan antiquity was not a harmless fantasy but a justification for conquest and extermination. Nationalist regimes throughout the twentieth century have pressed historians into service, fabricating ancient continuity or inventing legendary origins. Even today, myths of a ‘lost golden age’ are mobilised in political rhetoric across continents.

Hannah Arendt warned of the danger when the line between fact and fiction dissolves: ‘The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction… no longer exists.’ (The Origins of Totalitarianism). Pseudo-history erodes precisely that distinction. It is not merely false; it is corrosive, preparing the ground for authoritarianism by blurring truth and fiction. Thus, when we dismiss Atlantis or ancient aliens as harmless entertainment, we underestimate the stakes. The past, rewritten in false terms, becomes a tool of present domination.

Here, then, I must confess my own weariness. It is not easy to spend years labouring over manuscripts, only to have readers discard them in favour of a forty-minute documentary on YouTube that claims Julius Caesar was a time traveller, or that Rome was founded by refugees from outer space. The emotional toll of seeing spectacle displace scholarship is real. What makes it disheartening is not disagreement. I welcome debate; the clash of interpretations is the lifeblood of history. What wears me down is the displacement of history itself, the way myths crowd out the real work of reconstructing the past. There is nothing more dispiriting than a student who arrives eager for Atlantis, but finds Livy or Ammianus dull in comparison. And yet, this is precisely why we must resist. Weariness cannot give way to silence.

What Can Be Done?

The problem is formidable, but not hopeless. Several remedies present themselves.

Popper’s insistence on falsifiability remains a crucial safeguard. We must remind readers that theories which cannot be tested, challenged, or disproven are not historical theories at all. Hume’s scepticism should be part of every historian’s toolkit: an alertness to the human tendency toward wonder and credulity.

History must be taught not only as a body of facts but as a discipline of method. Students should learn how evidence is weighed, how sources are evaluated, how bias is detected. Richard Evans, in In Defence of History, rightly emphasised that history is not the same as fiction; it rests on disciplined engagement with sources. If the public were better trained in these skills, pseudo-history would have less appeal. Historians cannot retreat into the ivory tower. If we write only for one another, we leave the public sphere open to pseudo-historians. The challenge is to write accessibly without sacrificing rigour, to show that the true past is complex, messy, human and is more fascinating than any fabrication. The best antidote to pseudo-history is compelling, well-told, evidence-based history. The age of social media has amplified pseudo-history beyond anything Gibbon could have imagined. We must arm readers with tools to assess sources critically, to ask who is producing a video, what evidence is offered, and what motives may ie behind it. Just as citizens are taught to detect misinformation in politics, they must be taught to detect pseudo-history.

Finally, historians must not cede the realm of wonder to pseudo-science. The real past is filled with marvels: the engineering genius of Roman aqueducts, the intellectual ferment of the Greek city-states, the resilience of cultures long dismissed as “barbarian.” If we can tell these stories with passion, readers will see that history itself, honestly told, contains more awe than Atlantis ever could.

Why is pseudo-history so prevalent? Because it flatters our craving for simplicity, for wonder, for stories that confirm our identities or political ambitions. History is vulnerable because it cannot be replicated in laboratories, and because its evidential gaps invite fantasy. And yet, if we allow pseudo-history to prevail, we surrender the past to illusion, and the present to manipulation. The remedy lies in scepticism, in philosophy, in education, and above all in engagement. We must keep showing that the truth of the past, however partial, however provisional, is richer and stranger than the myths that obscure it.

I am weary, yes. But history deserves better than shadows and myths. And so, I think, do we.

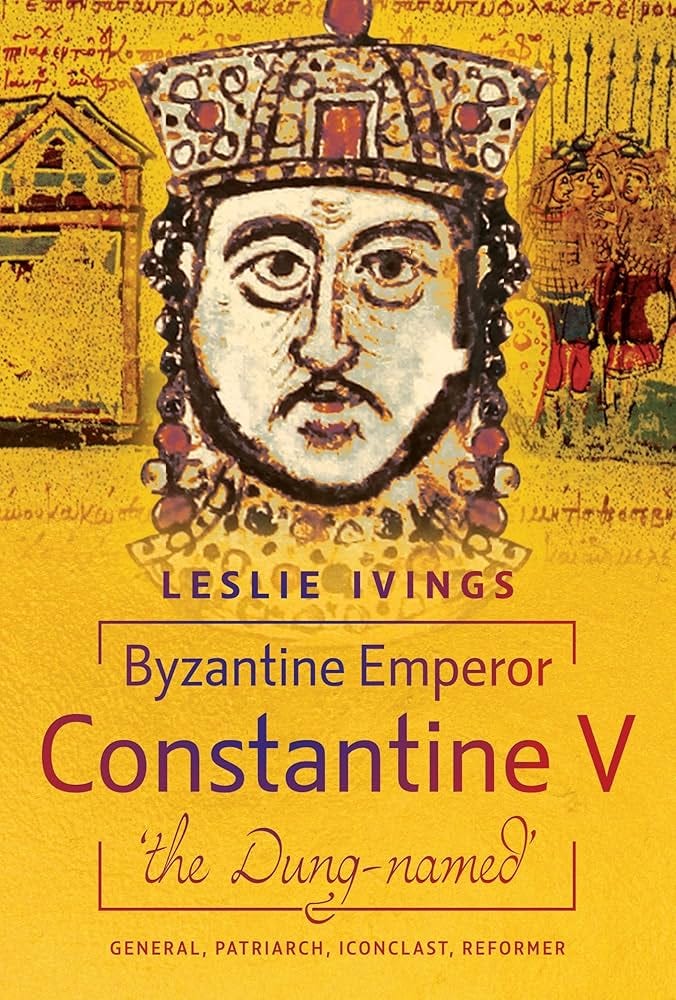

Featured image: Illumination of a 15th-century manuscript of Historia Regum Britanniae showing king of the Britons Vortigern and Ambros watching the fight between two dragons. (Public Domain)

Leslie Ivings is the author of Byzantine Emperor Constantine V, Pen & Sword (2025)

Constantine V - warrior, reformer, and one of Byzantium’s most formidable emperors. A brilliant general who crushed the Arab advance, strengthened the crumbling empire, and won the loyalty of his soldiers long after his death.

But history has not been kind. A fierce iconoclast, hated by the church and smeared by monastic chroniclers, he was branded Copronymos (“the dung-named”), compared to a sorcerer - even the Antichrist.

Married three times, politically astute, and as influential in theology as he was on the battlefield, Constantine’s legacy rivals Justinian himself. Yet unlike Justinian, he died not in splendour, but leading his army on campaign in Bulgaria.

Greetings friend.

Interesting post, I’ve been seeing your posts pop up for quite a while now.

Given what you share, i thought you may enjoy what I do.

I share a look at obscure histories, the ones left out of mainstream interpretations.

Here’s my latest, continuing on in my recent series regarding Giants:

https://open.substack.com/pub/jordannuttall/p/a-historical-record-of-giants-2?r=4f55i2&utm_medium=ios