Rediscovering Julius Nepos’ Dalmatian Court: Archaeology and the Last Roman Emperor in the West

Guest Article

For much of the past century, Julius Nepos has been remembered primarily as a footnote in the collapse of the Western Roman Empire. Overthrown in 475, he ruled in Dalmatia for nearly a decade before his assassination in 480. Yet recent archaeological discoveries are beginning to illuminate the reality of his court, offering tangible insights into what life was like for the last emperor to claim Rome’s western throne.

Dalmatia, far from being a peripheral backwater, was a vital region in the late fifth century. Its fortified towns, maritime connections, and agricultural wealth provided a strategic base from which Nepos could maintain his claim to Italy, coordinate diplomacy with Constantinople, and manage local elites. Until recently, our knowledge of this period came almost exclusively from literary sources: the chronicles of Marcellinus Comes, Priscus, and the fragmentary writings of Eastern historians. While valuable, these texts leave much to the imagination. Archaeology now allows us to see Nepos’ world in material terms.

Recent excavations in Salona (modern Solin, Croatia), the Roman provincial capital and likely administrative centre for Nepos, have uncovered layers of late Roman fortifications and domestic architecture dating to the late fifth century. Walls previously thought to have been abandoned in the early fifth century show signs of rapid repair and reinforcement, consistent with Marcellinus’ account of Nepos’ efforts to defend his territory against internal rivals and external raiders. Ceramic and coin finds further support an active, organized court: coins bearing Eastern imperial imagery alongside remnants of imported pottery suggest that Nepos maintained connections not only with Constantinople but also with Mediterranean trade networks, ensuring that Dalmatia remained economically vibrant despite political upheaval in Italy.

Smaller settlements and rural villas along the Adriatic coast reveal a similar pattern. Excavations at Trogir and Split have identified elite residences with mosaics, hypocausts, and evidence of ongoing agricultural production. These villas likely served as secondary residences or administrative hubs, enabling Nepos to project authority across the province and provide for his retinue. The material record demonstrates that the emperor’s administration was far from idle: local economies were maintained, taxes collected, and social hierarchies preserved.

Perhaps most fascinating are the recent finds of late fifth-century inscriptions and seal impressions. Some of these suggest that Nepos actively engaged in formal administration, issuing official correspondence and legal orders. While the texts are fragmentary, they indicate a functioning bureaucratic apparatus reminiscent of that in Ravenna, reinforcing the view that Dalmatia was not merely a refuge but a seat of legitimate power. Nepos’ court, in effect, continued the traditions of Roman governance even as the Italian heartland slipped from imperial control.

These discoveries also illuminate daily life. The presence of imported ceramics, fine tableware, and evidence of specialized craft production, particularly metalwork and textile processing suggests that Nepos’ court was culturally sophisticated, blending Roman, Mediterranean, and local Illyrian influences. Rather than a desperate exile clinging to a fading title, the material record portrays a ruler capable of sustaining a functioning, prosperous court far from the former imperial capital.

Importantly, these findings challenge the long-standing narrative of Nepos as a marginal figure. Traditional histories emphasize his overthrow by Odoacer and the swift absorption of Italy into barbarian domains, portraying Dalmatia as a backwater. Archaeology, however, offers nuance. It shows that Nepos’ Dalmatian court was not a shadow of imperial power but a continuation of Roman governance and culture in a peripheral region, one that maintained administrative coherence, economic stability, and diplomatic ties to the Eastern Empire.

For historians, these discoveries are transformative. They allow us to reassess the collapse of the Western Empire, not as a single catastrophic event, but as a process in which pockets of Roman authority persisted, adapted, and endured. Nepos’ court in Dalmatia stands as a testament to the resilience of imperial structures and the capacity of regional centers to sustain governance, trade, and cultural life in the face of systemic collapse elsewhere.

As excavations continue, we can expect even more light to be shed on this fascinating period. Each coin, ceramic shard, or fragment of inscription is a piece of the puzzle, revealing a Dalmatia that was vibrant, administratively complex, and politically significant under the last Roman emperor of the West. Julius Nepos, long relegated to the margins of history, is slowly being rediscovered, not merely as a man in exile, but as a ruler whose court kept the machinery of empire alive at the edge of the old Roman world.

Feature image: Illustration depicting the Palace of the Roman Emperor Diocletian in its original appearance ca 1912 by Ernest Hébrard. (Public Domain)

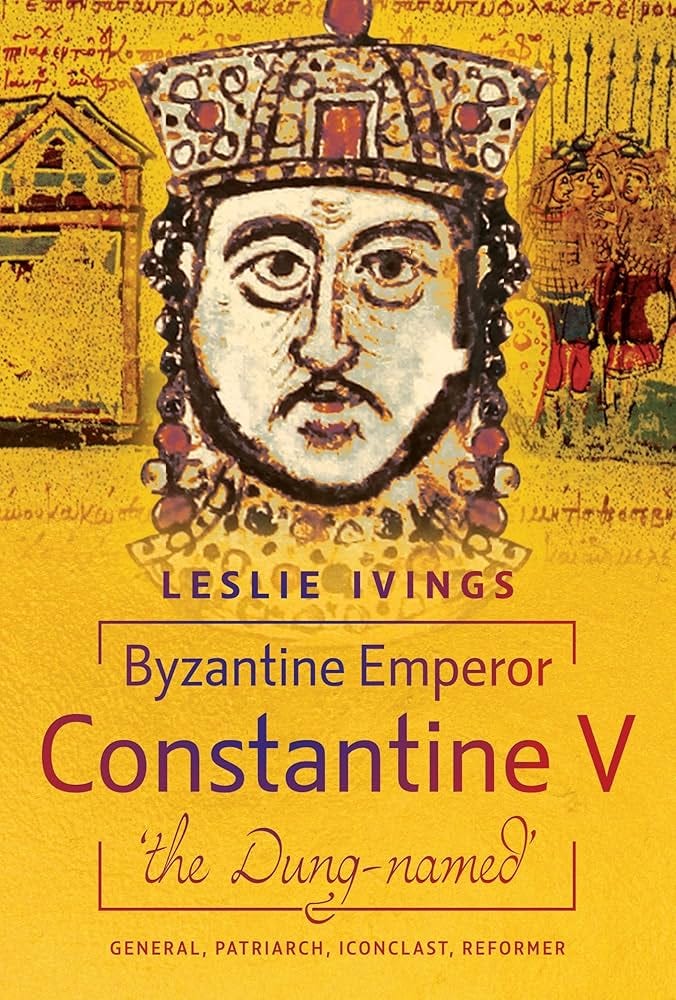

Leslie Ivings is the author of Byzantine Emperor Constantine V, Pen & Sword (2025)

Constantine V - warrior, reformer, and one of Byzantium’s most formidable emperors. A brilliant general who crushed the Arab advance, strengthened the crumbling empire, and won the loyalty of his soldiers long after his death.

But history has not been kind. A fierce iconoclast, hated by the church and smeared by monastic chroniclers, he was branded Copronymos (“the dung-named”), compared to a sorcerer - even the Antichrist.

Married three times, politically astute, and as influential in theology as he was on the battlefield, Constantine’s legacy rivals Justinian himself. Yet unlike Justinian, he died not in splendour, but leading his army on campaign in Bulgaria.

This right here is why archeology is so important. While the written record is great it can also be misleading through lost writings, unconscious bias, and straight up lying and misinformation. Archeology is one of the sure ways to support or disprove written sources. Thank you for the great read.

Thanks for sharing this interesting article.